THE BEAST GOES ON: Aleister Crowley & Rock

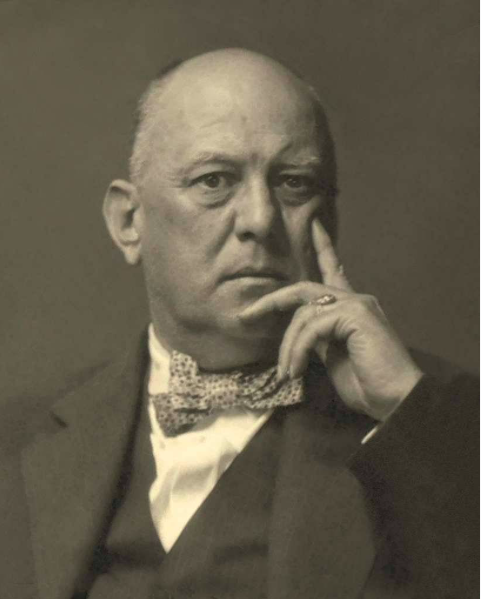

A SEARCH ONLINE will turn up scores of songs called “Do What Thou Wilt”. Jay-Z even sported the words on a T-shirt. The phrase was coined by Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) known, much to his own amusement, as the Great Beast 666, the Wickedest Man in the World.

Born into a wealthy family of fanatical Christians, Crowley rejected their beliefs and spent his youth travelling the world, climbing mountains, canoodling with scores of male and female lovers, and experimenting with every drug under the sun. He was a writer, poet, painter, and arguably the greatest exponent of the occult of the twentieth century. He was also a spy, employed by British Intelligence agencies throughout his lifetime, a fact I have explored in two books.

“Do What Thou Wilt”, is not an invitation to do anything you like, but instead a call to discover who you truly are and what you should be doing and applying your will to that end. It certainly appealed to the American rapper Ab-Soul who used it for the title of his 2016 album. In a YouTube clip, the rapper cites Crowley’s influence on the Beatles and Led Zeppelin as the key to his own interest. But the Beast’s impact can be traced much further back than that.

Born in 1923, Harry E. Smith was a visual artist and filmmaker, who compiled the iconic Anthology of American Folk Music, drawing from his extensive collection of out-of-production 78 rpm recordings. Issued in 1952, these songs had a huge influence on the folk scene and artists such as Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. A beat and an eccentric, Smith was also a life-long occultist who was consecrated as a bishop in Crowley’s church, The Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica.

Another early disciple was Joe Meek, Britain’s answer to Phil Spector and composer of the revolutionary worldwide hit ‘Telstar’. Said to be Margaret Thatcher’s favourite record, it was made in the ramshackle home studio Meek built in his flat on the Holloway Road. A brilliant and innovative record producer, Meek’s judgement was occasionally flawed, a fact not unconnected with his huge intake of amphetamines and barbiturates. He told Brian Epstein not to take on the Beatles and asked The Raiders to get rid of their hoarse, rubbish singer, 16-year-old Rod Stewart. The Raiders then became the Moontrekkers, who recorded ‘Night of the Vampire’, complete with creaking coffin lids and an authentic Joe Meek scream, that was stopped at number 50 in its march up the hit parade by the BBC banning it due to its effect on people of a nervous disposition.

Highly neurotic and temperamental, Meek was brought up as a girl for the first four years his life – his mother had wanted one – and was gay at a time when the penalties were severe as he learnt to his cost when arrested for importuning in a public lavatory. His erratic behaviour was legendary. After groping Tom Jones, he trained a starter pistol on singer and band to make them play what he wanted. He held a shotgun to the temple of drummer Mitch Mitchell – later of the Jimi Hendrix Experience – to compel him to play a drum pattern correctly. Meek had a passion for spiritualism, Crowley, and the occult, planting microphones in graveyards, and was convinced he could communicate with a talking cat and aliens. He held seances to contact the spirit of Buddy Holly, whose death on 3 February 1959 he claimed to have foreseen. On the same date in 1967, after first shooting and killing his landlady, who had frequently complained about the noise, Meek reloaded his shotgun and trained it on himself.

A similar gory end awaited our next Crowley acolyte, the R & B multi-instrumentalist Graham Bond, who introduced the mellotron and Bach to popular music. Bond was adopted at birth and grew obsessed with Crowley in his teens. Finding the Beast had spawned an illegitimate son in his home county, Essex, Bond inevitably concluded Crowley was his dad. After Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce left the Graham Bond Organisation to join Eric Clapton in Cream, Bond increasingly devoted his music to magick, producing tracks such as ‘Love is the Law’. Drug ravaged, stricken by financial and relationship troubles, Bond threw himself under a tube train in Finsbury Park Station in 1971.

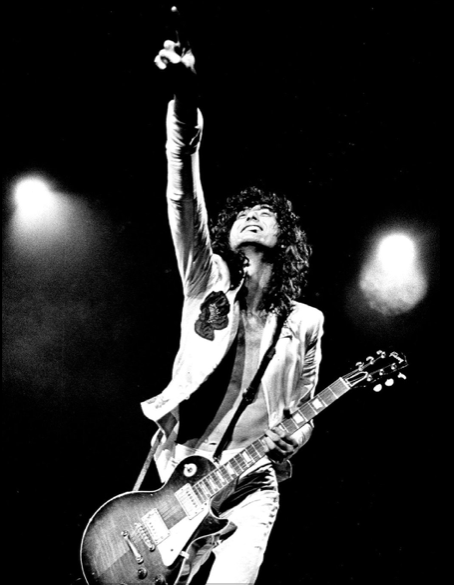

Bond had performed with Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, the school for so much Sixties’ rock. So had Jimmy Page, the best known of Crowley’s adherents, who also worked with Joe Meek as a session musician. Page opened an occult bookshop in Holland Street, Kensington called The Equinox and bought Crowley’s old home on the shores of Loch Ness, Boleskine House. The Led Zeppelin film, The Song Remains the Same, in which Page played a magician, was filmed there. Rumour connected the disasters that befell Led Zeppelin – the tragic death of Robert Plant’s young son and that of John Bonham, the drummer – with Page’s dabbling in the dark arts. Cowley’s influence is only subtly present in the music of Led Zeppelin, though Page did have “Do What Thou Wilt” inscribed on the vinyl of Led Zeppelin III. He dismissed claims demonic chants and invocations can be heard if you play the records backwards: it was enough of a challenge to play the music the right way round he pointed out.

Page made a very Crowley-influenced soundtrack for Kenneth Anger’s film Lucifer Rising. Anger was an American filmmaker and Crowley true believer, remembered principally for the lurid tales of celebrity scandal in his bestseller Hollywood Babylon. Anger hung out with the Rolling Stones during their ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ phase. Mick Jagger composed a soundtrack for another of his films. Page and the Stones also recorded a 1973 track together called ‘Scarlet’, the Scarlet Woman being a key concept in Crowley’s system.

Page and Anger had a dramatic falling out. The American director put a curse on the musician. Allegedly, Page did the same to our next Crowley obsessive, David Bowie. Bowie was another musician whose potential Joe Meek had failed to register. He and Page recorded together in 1965 and became friends. Page gave Bowie the martial riff for his 1970 song ‘The Supermen’. Things turned sour when Page visited the New York Townhouse where Bowie was staying in 1975, the peak phase, allegedly, of mutual cocaine use. Bowie was skeletally thin, living on milk and red peppers and obsessed by magick and occult Nazism. He believed Page was playing supernatural mind games and asked him to leave by the door or the window, the latter either in anger or in tribute to Page’s powers as a magician as they were on an upper floor. Terrified that Page had cursed him and might have gained possession of a fingernail, some urine or a strand of hair to ritually use against him, the story has Bowie immediately fleeing to the West Coast.

Page, allegedly, also put a curse on Eddie and the Hot Rods after they used a picture of Crowley wearing a comical pair of Mickey Mouse Ears to advertise their 1977 single “Do Anything you Wanna Do”, which demonstrated Crowley’s impact on punk was as profound as it had been on hippiedom. The band were almost immediately dropped by their label and various other disasters are claimed to have befallen them.

Bowie’s connection with Crowley was nuanced as the 1971 track “Quicksand” demonstrates. “I’m drawn unto the Golden Dawn, immersed in Crowley’s uniform of imagery” Bowie sings, the Order of the Golden Dawn being a late nineteenth-century magical organisation in which the poet Yeats waged magical warfare with the Beast. Though fond of emulating Crowley by dressing up in ancient Egyptian costume – Billy Eilish sported a photo of him so attired on her T-shirt at 2022’s Glastonbury – Bowie feels he is pulled between the light and dark, hardly surprising when you consider the fates of Joe Meek and Graham Bond.

Bowie took things even further on 1976’s Station to Station, a tour de force of an album he claimed he had no memory of making, where he references the Cabbala and White Stains, a book of pornographic poetry Crowley penned. Over time Bowie’s enthusiasm cooled. He would regret falling into the trap of “black magic, cabbalism and the Crowleyism of the times” – the mid-1970s – and dismissed, “That whole dark and rather fearsome never-world of the wrong side of the brain”. This does not tell the whole story. Some maintain the lyrics of his worldwide hit ‘Let’s Dance’ derive from a Crowley poem. The connection is tenuous. Less so is Crowley’s influence on Bowie’s remarkable farewell. The video for ‘Blackstar’, itself directed by a Crowley enthusiast, is packed with magical imagery. Lines such as ‘a solitary candle at the centre of it all’ echo Crowley’s Sapphire Ritual. In the video for his leave-taking song “Lazarus”, Bowie poignantly exits into a wardrobe dressed in the same bodysuit he wore for astral travel in Los Angeles in the 1970s.

A byword for Satanism, though arguably not a Satanist, Crowley has predictably had a huge impact on Metal. Iron Maiden’s ‘Moonchild’ is inspired by the Beast. Their lead vocalist, Bruce Dickinson, brought out a film called Chemical Wedding in 2008 in which Crowley reincarnates in the body of a Cambridge professor played by Simon Callow. Ozzy Osbourne described the Beast as a “phenomenon”. Enthused by Crowley-designed tarot cards in the studio – the pack of Thoth – he and a couple of bandmates wrote ‘Mr Crowley’. The song views the Beast as a tragic figure and ingeniously rhymes ‘pure’ with ‘rapport’, the former a nod to Crowley’s gnostic belief he could immerse himself in depravity and emerge smelling of roses.

Further afield, Raul Seixas (1945-1989), known as the ‘Father of Brazilian rock’ was introduced to Crowley in the 1970s by Paulo Coelho, who would achieve worldwide fame as the author of The Alchemist. Together they wrote a huge hit which translates as ‘Long Live the Alternative Society’, which references Crowley. They planned to create an anarchist free state based on ‘Do what thou wilt’ in the province of Minas Gerais. Instead, they were arrested and imprisoned by the ruling military junta. Seixas would recite Crowley’s declaration of rights, Liber Oz, at concerts. Every year on his birthday, thousands parade through the streets of downtown Sao Paulo to commemorate the man they call ‘Maluco Beleza’, which loosely translates as ‘Groovy Nutcase’. Seixas’s YouTube homage to Crowley, ‘Loteria de Babilonia’, is interspersed with animated images of the Beast.

Crowley’s modern-day followers are particularly concentrated in America, where Daryl Hall and Lady Gaga have been receptive to his teachings. In 1991, Red Hot Chili Peppers brought out their breakthrough album ‘Blood Sugar Sex Magik’. Their guitarist, John Frusciante, has also included the Beast’s texts on solo albums. Sex magick is the belief that by focusing your will on a specific objective during lovemaking you can bring about the required result. It is a key ingredient of Crowley’s system. Nearer home, Damon Albarn made use of a recording of Crowley’s voice in his 2014 opera Dr Dee. Dee was the court magician of Elizabeth the First as well as one of her principal spies. He believed he had mastered Enochian, the language of the angels, and Crowley can be heard reciting this on the track ‘Edward Kelley’.

Crowley believed a new age of childlike rebellion would really kick in around 1965. Coincidentally or not, 1965 is viewed as Year Zero for the great musical leap forward of the psychedelic era. The Beatles put Crowley on the cover of Sergeant Pepper. John Lennon said that “do what thou wilst” (sic), was what the band were about. According to Richard Kaczynski, citing an interview in Rolling Stone, Paul McCartney claimed that magic held the Beatles together, adding he meant magic with a k, which is how it is spelt in Crowley’s system to avoid confusion with more common-or-garden conjuring.

It is not hard to understand Crowley’s appeal for musicians. Fifty years before the word ‘hippy’ was invented he was a free-loving, drug-taking, commune-living, east-meets-west yogi spreading a gospel of personal liberation. That doctrine, usually compounded by heavy drug use, had a disastrous effect on Joe Meek and Graham Bond. But does that invalidate the music that Crowley or his school of thought inspired?