Richard C McNeff

Author

On This Page

Sybarite among the Shadows (short story)

Crowley & Huxley – A Trip in Berlin? (Fortean Times article)

Sybarite among the Shadows

Introduction

SYBARITE AMONG THE SHADOWS, the short story, was originally published in International Times, the newspaper of the counterculture, in 1977[1]. The story was inspired by a passage in Francis X. King’s Ritual Magic in England which asserted that Aleister Crowley introduced Aldous Huxley to mescaline in pre-war Berlin. I found the notion of such contrary types sharing so singular an experience intriguing. IT was having an identity crisis as publication coincided with the advent of punk. In one room, in the house in Notting Hill Gate that, for want of a better word, served as the broadsheet’s headquarters, the editor Max Handley and his crew were keeping the freak flag flying. In another, Scratch, a nascent punk magazine, was being cobbled together. Editorial meetings commenced with a rousing blast of the Sex Pistols.

My story caused a bit of a stir. Something I hadn’t banked on happened: people thought it was true. Books of the conspiracy variety focusing on the occult and esoteric Nazism quoted from it liberally. In the Eighties, it was republished by Rapid Eye, first in magazine form and then in a compendium. It was pirated. A doctored version appeared in Russia during the upheavals of the early Nineties. Many Russians thought it was true.

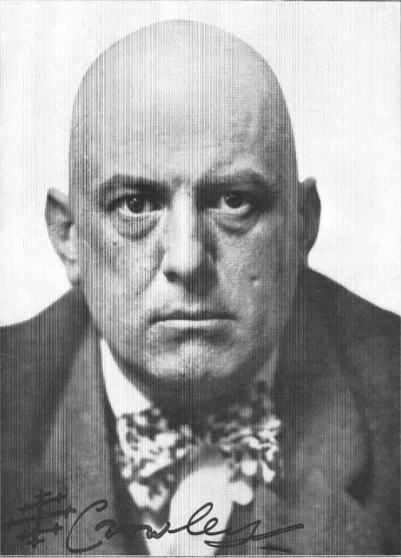

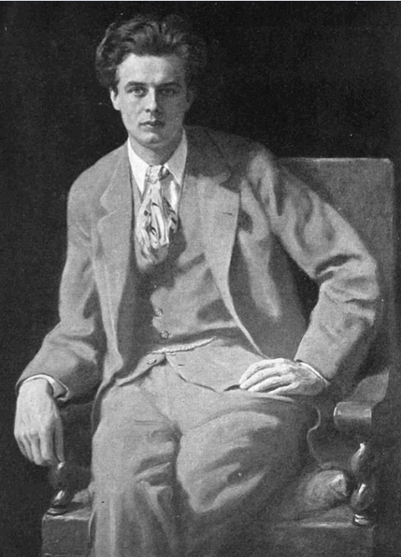

Crowley was living in Berlin in 1930 and spent three days with Huxley when the writer visited. Whether they partook of mescaline is a matter of some controversy. You can find a detailed discussion of this in a Fortean Times article reproduced on my website called ‘Crowley and Huxley: A Trip in Berlin?’

[1] This can be found in the IT Archive at 1977-07-01 – Volume – Q Issue 11

SYBARITE AMONG THE SHADOWS

“He bridges the gap between Oscar Wilde and Adolf Hitler” – Cyril Connolly

BERLIN. THE YELLOW STARS DAUBED on shop windows in the Jewish Quarter, overshadowed by the monstrous towers the Nazis called architecture – totems of the thousand-year Reich. Such a millenarian atmosphere suited Crowley, fresh, if that is the word, from a reinvigorating interlude of sex magick with a woman half his age in Lisbon. Like a gratified parent, he still doted on the “German Crusade”, as he called it. In turn, the authorities tolerated his existence. Names he had been invoking for years were on the lips of high-ranking SS officers: Ahriman, Horus, Moloch – many gods were abroad that year. Besides, his relationship with the Nazis stretched back to the early days of the Party’s formation. Yet they did not like the relationship to be too defined. Already theirs was a hidden doctrine, a sect of intrigue and the esoteric, of ritual and symbol, posing as modern.

A few years later, his eyes opened, his order, the OTO, suppressed in Germany, Crowley would describe them with contempt as the Black Brothers. Indeed, they were worshippers of the left hand, the perverted spirit — but in secret only. To the world of appearances, they presented themselves as the final cult of the empirical. Crowley to them was a buffoon, performing in a shadow play of rich widows and cocaine. He shared their interests but not their intent. The Wanderer of the Waste was comfortable with this arrangement. He loved outrage and extravagance. For them, purpose was enough.

Crowley had first met Aldous Huxley in this same Berlin at the start of the decade and had painted his portrait in the belief that the writer was rich. This time Huxley was in the city as an observer of the strange monster Germany was becoming. Like many witnesses, he was both repelled and fascinated by the dark pulse that beat through the nation. To describe their relationship as friendship would be to miss the point. Crowley was doubtless fascinating — notorious as the Great Beast 666 in his own country and much of Europe, a brilliant conversationalist and something of an enigma, whereas Huxley was a myopic intellectual. Yet Crowley attracted him, just as thirty years before he had intrigued peevish Somerset Maugham in Paris. He almost existed for the straying eye of the novelist who hunted those chapters of exhibition life did not afford. Yet now Crowley fades, his rotundity, absurd and menacing, is blurred – a glaring headline of Edwardian sin.

“Do what thou wilt is the whole of the Law.

Love is the law, love under will.”

I utter his Law in my defence, that simple phrase filched from Rabelais, supposedly dictated in the mirage of a Cairo night by his guardian angel Aiwass. I think of him towards the end of the war, shambling through that seedy Hastings boarding house, sated with the Law: a figure of pathos in his threadbare dressing gown, nursing his habits and remorse, an agèd minotaur, sybarite among the shadows, in the fading of his Aeon more the Fool than Prospero.

Already in the Thirties psychotropic agents fascinated Huxley. Albert Hoffman, synthesizer of LSD, had yet to sway on his bicycle after the mysterious drug seeped through his pores, yet there existed an abundance of literature concerning its forerunners: Havelock Ellis’s experiments with mescaline or those of William James with psilocybin. Moreover, Berlin, at that time, still nursing its Weimar hangover, was the epicentre of drugs in Europe. Both Hitler and Goering used amphetamine and cocaine, and the SS administered narcotics in their initiation ceremony, the Ritual of the Stifling Air, which closely resembled a Black Mass. Indeed, one of the biggest contributors to the formation of the Nazi Party, and so the Second World War, must have been the diet of methedrine, a super strength amphetamine, and Nietzsche fed to German soldiers in the trenches – pills along with copies of Also Sprach Zarathrustra were standard army issue. An oversimplification, perhaps, yet the first pharmaceutical history of our epoch remains to be written.

Thus, Huxley came to Crowley for his first taste of mescaline. The latter took the drug irregularly, without pretensions, purely as an exercise in that hedonistic spirituality he preached as well as practised. On the other hand, Huxley nursed a genuine mystical longing that had surprisingly blossomed in a soul as rooted in reason as his own. There was a confusion of aims, a perennial ambiguity about their enterprise. I, Victor B. Neuburg, poet and sodomite, sorcerer’s apprentice, veteran of the angel magic at Bou Saada and Jupiterian visitations of the Paris Workings, was the arbiter.

They had spent the afternoon in our less-than-opulent lodgings discussing karma. Crowley was talking:

‘To me, it exists solely as a paradox. It is true I have seen retribution visit others on many occasions, especially those foolish enough to cross me, as they have learnt to their cost. There does seem to be balance in the machinery. Nevertheless, this process is unending. It acts in everything and so to allow it an iota of acknowledgement is absurd.’

‘We reap what we sow, Aleister,’ Huxley countered, ‘not in a moral sense, at least only haphazardly moral. Nemesis is something like gravitation, inevitable yet indifferent. If, for example, you sow self-stultification by an excessive interest in money, you will engineer a grotesque humiliation.’

‘In what sense? How can you possibly ascribe humiliation to the rich? They’re the last people to fall victim to that failing.’

‘I was coming to that. By self-stultification, I don’t just mean money. I mean anything that clouds the spirit. Over-indulgence in alcohol, food or sex are more examples of things that wreck our purpose. However, because these things reduce you to the sub-human, you will not be aware the humiliation is humiliation, so to speak. There is your explanation of why nemesis sometimes seems to reward. What she brings is humiliation only in the absolute sense, for the ideal and complete human being, or at any rate, for the nearly complete. For the sub-human, it may seem a triumph, a consummation, a fulfilment of the heart’s desire.’

‘Moral,’ concluded Crowley,’ live sub-humanely and nemesis may bring you happiness. Well, if you will excuse me, my dear Aldous, I will proceed to self-stultify. Victor, if you don’t mind: Pandora’s box!’

I rose, went to the cabinet and took out his medicine. Four phials lay in the ivory box. I selected the one containing Burmese heroin, and another crammed with Bolivian cocaine. Carefully I mixed the powders on a silver tray, crushing the dirty khaki-coloured heroin and adding about five times as much cocaine. I passed Crowley a silver spoon that, with surprising dexterity, he used to scoop up some of the powder, which he then deftly inhaled, first through the right and then the left nostril.

‘Won’t you join us for cocktails?’ Crowley invited. ‘This mixture certainly beats Pimm’s.”

Disapproval etched itself into the lines on Huxley’s drawn austere face.

Observing this, Crowley commented: ‘I’m afraid if you keep the devil’s company you must see his works. Imagine you’re with Falstaff: “Gentlemen of the shade, minions of the Moon”.’

‘But this is such waste,’ declared Huxley, ‘the ultimate form of self-stultification. What’s more, I’m sure it’s a conscious assault on the soul, an immense dereliction and act of self-harm.’

‘It depends. Drugs are magick and have always been used as such. The soma of the Vedas, the nepenthe of Homer, the henbane and the belladonna of the witches, all point to the fact. I am sure for the normal man, whom I happily call the sub-human, they are invariably detrimental. However, in no way do I consider myself ordinary. To me, drugs are the litmus test of capacity. I know the wraith-like effects of cocaine, that long corridor of shadow where the soul is wasted and profaned. And heroin! The cushioned daze of the opiated night. But it is because I have supped large on such joys and sorrows that I consider myself more than human.’

‘Haven’t you read Baudelaire’s intimate journals? Isherwood, who is staying nearby, has just translated them. I’ve never come across such desperation, such remorse for a lifetime given over to false ideals, hashish and all the other indulgences that ruined the Decadents.’

‘But that is it exactly!’ Crowley was excited by the drugs. ‘Baudelaire gloried in his fall, his self-imposed damnation. Besides, he did write some damn fine stuff, and wasn’t that born precisely out of those feelings of failure and hysteria he cultivated with his drug taking, his black bitch, his Catholic guilt? You see, Aldous, as long as we are active, we are saved. All energy is eternal delight provided we use it. To take a drug is to permit a daemon to enter the sanctum of thought and action. If we give voice to this captured spirit, we enforce, rather than profane, and so exorcise the very spirit that possesses us.’He got up and went over to the sideboard. It was growing dark outside. His obesity threw a giant shadow across the wall. I suppose, in tribute to the spirit of the times, I should record the stamp of stormtroopers’ boots from the street below. But in truth, I only heard the low growl of traffic and the occasional shout. Crowley came back and gave Huxley a piece of paper. ‘Read!’ he said simply.

I have that paper before me now. In the last decade, it has yellowed and grown brittle around the edges. It is one of many of his papers that I keep: bills, incantations, the occasional doodle or letter. Like me they survive in obscurity, unknown to both his followers and biographers. I shall transcribe it here.

“From the tower enchantment and the sweet hypnosis of lost time, my dream seed spill their valediction across known worlds. I tell the cartographers, who call my map invisible, that space is frozen in the habit of their fictions. Their cities are my seed, their houses, wives, and toil are fantastic shadows of solidity. I see only waves, brilliant, aural cartoons containing one inch of gross matter. Let the radiant language spill forth. I sing the chisel and the blade, the hammer and the scales, and all melodies of craft. The Work ferments inside my battery of cells. My voltage is a million watts.

“Alchemy is patient. It sits in stillness. Like Tao it recognises the divinity of hazard, the vigour of the useless – accident is merely the collision of two meanings. So, in me the dross solidifies. I have stopped asking if I have a story as there are no stories now, only decipherable collisions. In me, the opaque furniture of the random is condensed and drained into rich ore. My veins are heavy with dark coal nurturing diamonds. I am the Red King, the bronzed phoenix upon the wheel of flame. I have traversed the river of ordeal and am crowned by elementals. Now shall the paradox of prisms blaze onto papyrus my heart’s bold voice.

“Airborne visions tingle. Coming from rich flight, the dreamer’s wingspan – almost prosaic this whirlwind. Lost continents, contours, cartographers, and me, my maiden voyage is crystal and a glass. Truly it is the scheming polarity of vision this placing on a glass, a pane that mirrors to the heart’s dereliction, the soul’s migration. I sweep the city. This is the holy liquid of metropolis, fashioned in the image of its metal bowels. This is the Fall of Ushers, the corruption of sense. Tell me the sex of electricity, of coils, sockets, plugs. Once the planet gave godlike gender to the thunder in the hills. Only man creates the sexless. My mind is snow vapour; airwaves flow freely like the magic carpet on Sinbad’s voyage. I am standing in Mexico. I have the stature of the ancients, the children of Lilith, twenty-three feet tall. I strut the sunflower Van Gogh sand, eaten by cacti, while the arcane sun explodes above. I eat the sun. I am the debris of stars. Solar storms flare from my pores and launch a billion sun-borne seeds, the shudder running through me forever. In the fever of mirage, in hallucination, I seek to touch the brimming fare of yellow; peyote, datura, mescaline. Behind needles sharpened by white light, fantastic buds map shades of an oasis.”

Huxley read the piece carefully but seemed unimpressed. His exact words I cannot recall, only that they were polite and vague. Myself, I am fond of the passage, as I am fond of all visionary, otherworldly things. Doubtless, to Huxley, this was further proof of the Beast’s eccentricity, like the pantheon of dark, forgotten gods that sprang so readily to his lips.

‘When the wind of the wings of madness comes,’ Huxley said, ‘I hope you will be spared!’

His purpose in coming that evening was to take mescaline. They had discussed the subject at length – Huxley citing Havelock Ellis, Crowley the Vedas. ‘Come then,’ said the Beast as dusk fell. First, we smoked hashish in a hookah, its effect lightening the atmosphere considerably. Huxley lost most of the caustic self-possession that clung to him like a limpet to a rock. He grew jovial. Crowley’s mind still maintained the intense superficial clarity that cocaine induces and heroin and hashish only partially subdue. He teased our guest like a mischievous child. Huxley’s intellect was running wild. He talked scathingly of England and the English, expressing opinions that delighted Crowley. They discussed Gurdjieff and then Yeats and his Vision. This time it was Crowley’s turn to be scathing. ‘Weary Willie!’, he scoffed. Huxley even launched into a lecture on Tao exercises, which Crowley brought to an abrupt halt by asking if one-hand clap was a form of onanistic syphilis. We all laughed uproariously, like schoolboys over a dirty joke. Meanwhile, I had administered the mescaline.

‘You know Hitler has taken this stuff,’ Crowley observed. ‘I heard it from a reliable friend in the Thule Society. Their connections with the Nazis are nobody’s business. They almost founded the Party, or at least subverted it. Do you know that two of their top men personally trained Hitler? Before he was a stuttering Austrian oaf, a shoddy artist with dirty nails, a pervert to boot. They coached him in oratory and rhetoric, and under the influence of the drug that will shortly, my dear Aldous, set your eyes on fire, gave him his daemon.’

Crowley’s tone contained a certain malice – a hint to our absolute realist of the irrational and dark forces he might encounter.

‘Then,’ declared Huxley, ‘all the dispersed romanticism that in its waning found expression in the esoteric, in secret cults, has made its kingdom here; fascism is the terminus of decadence, the final madness of bohemia.’

‘So that Bartzabel, Spirit of Mars, may have his day, precisely,’ Crowley agreed.

Later a vast smile wreathed Huxley’s dry features, now radiant, illuminated, his eyes indeed tinged with fire. In what region of enchantment he wandered, I do not know. Whether beneath the icy domes of Kubla Khan or in some long-vanished field of his childhood, fragrant with wood smoke, he did not say. What music flowed inside him, whether the Abyssinian maid soothed him with her dulcimer, or the highest octaves of the stars astonished his ears, was also secret. Whatever is discovered at such moments belongs inviolably to the inner life of the voyager. Even if he should wish to convey it, he would probably find the few words that pertain to this region of experience unforthcoming. We have no maps for the mescal voyage of the psyche.

For me, it was a night of colours – yellow phantoms emanating from the streetlamps below; silver flashes of rain tangoing on the windowsill; the deep cobalt of the sky an airless backdrop to the unflinching stars; a violet gauze of cloud stretched over the white moon: all the world’s allure gathered in a rainbow.

At one point Crowley produced some Tarot cards. The figures seemed to move – the Lovers entwining themselves on the matrix, the Empress breaking into her impenetrable smile, the Prince of Wands tightening the reigns of the chimaera he rode. All these vital creatures, through our intent, in the steely point of time called Berlin, living out the correspondence of their ageless dance. Like a pharaoh long ago, we parted the curtain and glimpsed the peerless geometry of the stars.

At another point Crowley quoted from the Book of the Law: ‘I am the snake that giveth knowledge and delight and bright glory and stir the hearts of men with drunkenness. To worship me take wine and strange drugs, whereof I will tell my prophet and be drunk thereof! They shall not harm ye at all.’

‘A bit perilous, don’t you think?’ Huxley murmured.

‘Of course,’ Crowley agreed, always lucid when discussing his work, ‘if you read it carelessly and act on it rashly it might well lead to trouble. But the words “to worship me” are all important. They mean that things like cocaine, mescaline and alcohol should be used for worshipping, that is, entering into communion with the Snake, which is the genius that lies at the core of every star. For every man and woman is a star. The taking of a drug should be a carefully thought out and religious act. Experience alone can teach you the right conditions in which the act is legitimate; when it can assist you to do your will.’

Huxley left shortly afterwards. He walked through a Berlin he had never seen before, where cylinders of fire in the cold dawn air dazzled his senses, and the splashing rain grew into cartwheels of light spinning across the pavement. He had entered a hitherto unknown continent and now, an illuminated Columbus, was intent on discovery. I remained with the good Master Therion, his bulk shifting in reverie on the Turkish couch.

Many years stretch between that time and now. Long ago my two protagonists were dust, fallen to the bottom of the hourglass. Huxley on his deathbed: two hundred micrograms of LSD-25; the luminous smile of his chemical exit. Crowley in that rambling Hastings boarding house: a vast spider with a heroin itch, regurgitating the entrapments of the past. Many years: a war; the accelerated madness of an epoch; the dawning of the new aeon. To me long slow years of remorse, when I turned from the gender he had so skilfully taught me and from the vision that witnessed me abandoned in the desert: the pallid brow, stiff horns, the foul rapture that attends that angel to we in league with him through time and eternity: his sub-contractors.

CROWLEY AND HUXLEY – A TRIP IN BERLIN?

(originally published in Fortean Times September 2021)

In 1977 International Times, the flagship of the English underground, published ‘Sybarite among the Shadows’, a short story I had written based on Aleister Crowley initiating Aldous Huxley into the use of mescaline in Berlin in the 1930s.[1] For good measure, I spiced things up with a reference to Hitler using the drug. The story went on to be widely circulated, often without my knowledge. A doctored version appeared in Russia, and it was cited and quoted in books on conspiracy theory and occult Nazism, invariably presented as being true.[2] The story was based on a couple of lines I had found in a book by Francis King called Sexuality, Magic and Perversion. So widespread had the idea become that the Huxley Estate felt impelled to deny it:

“There is no evidence to support Francis King’s assertion that Aleister Crowley introduced Huxley to mescalin [sic] in Berlin in the 1920s [sic].”[3]

Despite this, Huxley’s alleged psychedelic encounter with the Beast has taken on the dimensions of an urban myth, and a quick perusal online will find it cited as fact on several websites, including those hosting the burgeoning number of academic books and papers devoted to Crowley. So, what did happen? Two recent, meticulously researched works by Tobias Churton[4] and Patrick Everitt[5] help provide an answer. Both offer tantalising evidence that if conscious expansion did not actually take place in practice, it was almost definitely explored in theory.

From the 1890s on Crowley had been interested in finding a ‘pharmaceutical, electrical or surgical method of inducing Samadhi’, as he put it in The Confessions. Of all the drugs he experimented with, the psychoactive alkoids extracted from the peyote cactus most closely fitted the bill. The active component is mescaline, known when Crowley started using it as Ahalonium Lewinii. Other members of Crowley’s magical order, the Golden Dawn, also experimented with it, notably Yeats and Maud Gonne. Yeats was impressed and found peyote more conducive to the production of visions than hashish, though he did not like the effect on his breathing.[6]

Crowley went on to become something of a proselytiser for the drug. In the debate that raged in the 1960s between those who believed in the wholesale distribution of psychedelics led by Timothy Leary, and those, like Huxley, who advocated confining their use to a circle of adepts, Crowley would probably have belonged to the former camp. In his Rites of Eleusis, held at the Caxton Hall in 1910, the paying audience were given a drink spiced with mescaline. The hapless – or happy – spectators were then entertained with magical ceremonies, poetry, dance, incense, and music. Between 1913 and 1917 Crowley hosted “Anhalonium parties” in London and New York in which he gave peyote to many figures from occult and literary circles, including the New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield and the American writer Theodore Dreiser. According to the account left by Crowley’s friend Louis Wilkinson, the Beast decided Dreiser merited three times the usual dose. Displaying great bravado, Dreiser drank this down in one gulp. He then had second thoughts and enquired if there was a doctor in the neighbourhood. Crowley was not sure but reassured Dreiser that there was a very good undertaker nearby.[7] Wilkinson himself saw visions in bright colours and found the drug “surprising and exciting” but the fact it made him sick afterwards restricted his use of it.

Crowley described Thelema, his belief system, as having the ‘aim of religion; the method of science’ and he kept detailed records of hundreds of experiments with peyote which in 1919 he advertised would appear in a forthcoming issue of his journal, The Equinox, along with an explanatory essay titled ‘The Cactus’. It was never published, apparently destroyed by British Customs in the 1920s. Crowley got the fluid extract of peyote from the American company Parke-Davis. He was actually given a tour of their “wonderful chemical works” in Detroit in 1915, where they made up a batch of the drug customised to his specifications. By 1920 they had stopped producing. However, peyote buttons, protrusions cut from the top of the cactus where the mescaline is concentrated, can in a dried form maintain their potency for decades.

On Thursday October 2, 1930, Huxley visited Berlin with the popular science writer J.W.N. Sullivan. This was at the behest of The Observer for which they were compiling a series of “Interviews with Great Scientists”. Sullivan was a friend of Crowley, who was also in Berlin, focusing on his career as a painter. Crowley found out they were arriving and the next day wired Einstein, who was then residing in a central Berlin loft apartment, in order to track them down. He eventually located them via the physicist Erwin Schrödinger, celebrated for his contribution to quantum theory and the “Schrödinger’s cat” thought experiment. Strange company indeed for a magician to be keeping!

Crowley dined with Sullivan and Huxley that night and then took them to the Mikado drag club to sample the local night life. The Beast got on well with Huxley and believed he had roused the latter from his usual apathy. Crowley spent the evening of the next day with the visitors in a beer hall, finding Huxley “charming” and that he “improved on acquaintance”. Sullivan drank too much iced beer and had a bad hangover on the Sunday, which Crowley spent with him and Huxley. The Beast was interviewed for the great men of science series, but it was not used, probably because such views as “every phenomenon ought to be an orgasm of its kind”[8] were a little too advanced, even for Observer readers of the period. The Beast painted the portraits of both men, which have been lost.

After their visit, Crowley wrote to his secretary Israel Regardie, who was in London. He described the three days he had spent with Huxley as “gorgeous” and asked Regardie to set up a figure for the horoscope he was making for Huxley, who had supplied the time and place of his birth. He also asked Regardie to send Huxley some of his poetry.

The book was called Clouds without Water and was published in 1909 when Crowley was experimenting with both hashish and peyote. It contains two references to cannabis and associates the drug with astral projection. Interestingly, in the letter and two cards that have survived from Huxley to Crowley there is a joke about astral projection, a magical practice that Crowley linked with both drugs. In an undated postcard from Provence, Huxley refuses an invitation from Crowley “for geographical reasons which I’m not yet far enough advanced in the Black Arts to nullify!” This suggests to Patrick Everitt that the two writers may have discussed Crowley’s early experiments with both drugs and by extension consciousness expansion.[9] An intriguing anecdote in Churton’s book lends support to this. A few months after Huxley and Sullivan’s visit, Karl Germer, the Beast’s German associate, wrote to “Crowley’s recently dismissed treasurer, Gerald Yorke, in London, suggesting Yorke persuade Aldous Huxley to return to Berlin to give a promotional talk about Crowley’s “consciousness-expanding work”.[10]

The first known instance of Aldous Huxley taking mescaline was on May 5, 1953, when he was 59. The following year he brought out The Doors of Perception which elaborated on the experience. Crowley had died in 1947. In 1954 his reputation was probably at its lowest ebb. John Symonds’ biography, The Great Beast, had appeared in 1951. While Symonds was instrumental in bringing Crowley back into the public arena, the biographer’s distaste for his subject, which he expressed in person to me, did little to mitigate the facile popular image of the Beast as a sex and drug crazed Satanist. Hardly the right ally for Huxley’s controversial advocacy of psychedelics as legitimate facilitators of mystical states with profound potential benefits for science, art and religion, his own use famously extending to the two injections of LSD-25 he received on his deathbed. Even if the Beast had supplied him with peyote during the three “gorgeous” days, it is hard to believe Huxley would have publicised the fact. Unless new evidence emerges, there probably was no trip in Berlin. Nevertheless, there were very likely to have been exchanges which helped seed Huxley’s later exploration of the psychedelic realms in which the Beast was a seasoned traveller. If so, Huxley and Crowley’s encounter represents a milestone in the history of entheogens and their impact on our times.

[1]http://www.richardmcneff.co.uk/page4.php

[2] See, for example, The Occult Conspiracy by Michael Howard (Inner Traditions, 1989) or The Nazis and the Occult by Paul Roland (Arcturus, 2007).

[3] Aldous Huxley, Moksha: Aldous Huxley’s Classic Writings on Psychedelics and the Visionary Experience, ed. by Michael Horowitz and Cynthia Palmer (Rochester, VT: Park Street Press, 1999), p. 3.

[4] The Beast in Berlin by Tobias Churton (Inner Visions Bear & Company, 2014).

[5] ‘The Cactus and the Beast’ Patrick Everitt. (M.A. in Western Esotericism Thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2014-16).

[6] Everitt, p. 27.

[7] Louis Marlow, Seven Friends (London: The Richards Press, 1953), pp. 57-59. ‘Louis Marlow’ was Wilkinson’s pen name.

[8] Yorke Collection, NS 18, “Questions put to E.A.C. by J.W.N.Sullivan.”

[9] Everitt, p. 44.

[10] Churton, p.225.

Made at the tip of Africa. ©