Richard C McNeff

Author

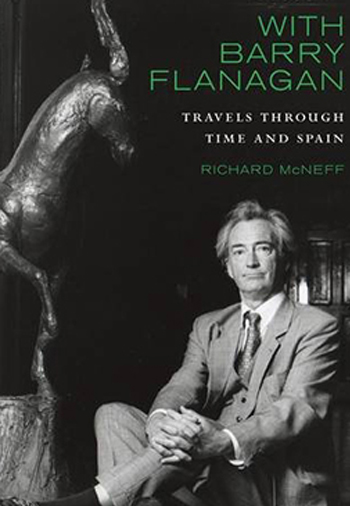

With Barry Flanagan Travels through Time and Spain (Lilliput Press)

A vivid account of a close friendship that evolved into a working relationship when Richard McNeff became ‘spontaneous fixer’ (Flanagan’s description) of the sculptor’s show held in June 1992 at the Museum of Contemporary Art on Ibiza, where they were both living. McNeff was to gain a privileged insight into the sculptor’s singular personality and eccentric working methods, learning to decipher his memorably surreal turns of phrase and to parry his fascinating, if at times unsettling, pranksteresque quirks.

In September 1992 Flanagan and McNeff took the show to Majorca, resulting a lively visit to the celebrated Spanish artist Miquel Barceló. The following year McNeff was involved in Flanagan’s print-making venture in Barcelona and in his Madrid retrospective. Flanagan rescued him from a rough landing in England in 1994 by commissioning a tour of stone quarries there. Subsequently McNeff ran into a fourteen-year-old profoundly deaf girl who turned out to be his unknown daughter. She had a talent for art and the generous sculptor was instrumental in helping with her studies.

Late in 2008 Barry was diagnosed with motor neurone disease. By June 2009 he was wheelchair-bound. Two months later he died, and McNeff read the lesson at his funeral. Fleshed out with biographical detail, much of it supplied by the sculptor himself, supplemented by photographs and details of the work, this touching memoir is the first retrospective of a major Welsh-born artist. With Barry Flanagan captures the spirit of this remarkable Merlinesque figure in a moving portrait that reveals a true original.

ISBN: 978 1 84351 322 3 – hardback (also in Kindle) – Lilliput Press

REVIEWS

“It is a very personal and often hilarious recollection of McNeff’s support of Flanagan … a compelling portrait of this great artist.”

Barbara Dawson: Irish Arts Review

“Your book is so rich in Barry-lore and response to his work that it more or less makes other biographies unnecessary.”

Catherine Lampert (former director of the Whitechapel Gallery)

“This book is chock full of ‘Flanagan anecdotes’ and as a reader I felt like I was being let in on a secret of these bohemian artists who had lived in Ibiza and their hippy and boozy lives. It is a fascinating account and whether you are familiar with Flanagan’s artistic work or not, this is an extremely interesting biography which is a great read that will leave you more knowledgeable about the artist as well as entertained by the stories.”

The Dublin Duchess

“A cracking memoir – funny, informative, elegiac and thought-provoking. Barry Flanagan cast leaping leporines, spent his final years on Ibiza and was born in Prestatyn (where I attended a wonderfully 1930s prep school), but these bare factoids are also connected with the fundamental laws of the Universe. He was actually a magician with words and ideas, and his playful probing into public minds and private lives was worthy of Gandalf himself. Ibizaholics will delight in McNeff’s expert skewering of island life and mores, while the artist’s hilarious two-step with museum directors and local hacks is sheer joy. The journey into Flanagan’s Jarryesque modus operandi is art writing at its best, self-deprecating prose that makes every page a delight. Lilliput Press have risen magnificently to the occasion with pruned-back design, a sensible typeface, nice, creamy paper plus a sprinkling of helpful illustrations. In short, like a glittering vernissage you cannot afford to miss.”

Martin Davies (founder of Barbary Press, Ibiza)

Miquel Barcelo and Barry Flanagan, Cerámiques i Dibuxos (ceramics and drawings)

Enrique Juncosa and Richard McNeff.

Published to coincide with the exhibition of the artists’ work at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Ibiza 27 of April to 31 October

2012. Contains my account of the artists’ first meeting in English, Spanish and Catalan.

Piece in the Guardian to coincide with Barry’s show at Tate Britain (27 September-2 january). There is also a picture gallery of his work.

‘Hare today, but not gone tomorrow’

(www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/sep/26/barry-flanagan-tate-britain-exhibition)

As Follows

1) Barry Flanagan: In Appreciation

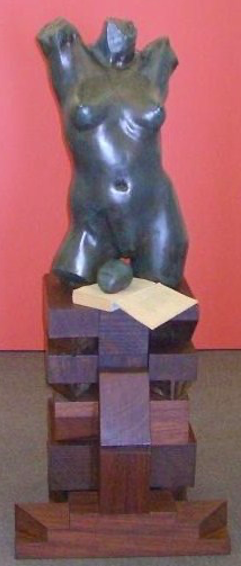

2) Head of the Goddess in my Hands (about the sculpture)

3) A Reduction of Invertigo (short story)

BARRY FLANAGAN: IN APPRECIATION

When I first saw Barry, at a wedding in Es Figueral in the late eighties, going by his dusty denim suit and general boho air, I judged him to be another of the many artists on Ibiza who eked out a modest, at times precarious living in pursuit of their calling. It was not until sometime later that I discovered he was an artist-star as celebrated in Tokyo as he was in London, Paris and New York.

Barry was born in Prestatyn, Wales, in January 1941. In his youth he tried his hand at labouring, the cello, quarry work, dental work, and making props on the film set of Cleopatra. All of these disparate callings appeared, in one way or another, in the work that began to emerge from his time at St Martin’s School of Art.

In the Sixties he was firmly associated with the avant-garde and worked in performance art, drawing, film and found art. His reverence for materials and form was immediately noticeable and he was equally at home with clay, cloth, rope, sand and stone. His work was also distinguished by evocative, playful titles such as Sixties Dish, a cello reflected by a mirror on a sofa. He narrowly avoided becoming the target of the kind of ridicule that was heaped on his friend the American minimalist Carl Andre, when the Tate bought the latter’s bricks, for works such as Barry’s own Pile, literally just that – a pile of differently coloured blankets. What marked the sculptor out as well was his humour and subversiveness, inspired to a considerable degree by the French writer Alfred Jarry, inventor of Pataphysics, the “science of imaginary solutions”. These qualities were implicit in the bronze hares he started modelling in the late seventies, which brought him rapidly into the public eye.

I once told him a talent such as his would inevitably find recognition and was surprised at how angry he became. Resentful of the way “money punishes art” and realising the Flanagan money he was producing, notes drawn and signed by him for £5, £10 and £20 pounds, had a limited spending power, Barry foreswore the clichéd pose of the artist starving in a garret, and took some business courses, anticipating Brit Art in his lack of squeamishness concerning success and wealth as well as in the remote method of production he favoured for the bronzes.

What began as a friendship between us took on a more workmanlike direction and I became his “spontaneous fixer” for a period in the early Nineties. Among other things, I assisted him on the show he shared with the French sculptor Marcel Floris at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Ibiza in 1992, which we later took to Palma. This in many ways was the equivalent of the Rolling Stones gigging in a local pub, but he set to with gusto and the results were fascinating. The word genius is bandied about with great freedom these days, but seeing him in action was a revelation, and being present when he was literally struck by an idea, a lasting privilege.

Barry passed away on August 31 after becoming afflicted with motor neurone disease. He has, in the words of Auden on Yeats, “become his admirers”. The obituaries speak of “Britain’s best-known and most controversial modernist” (The Daily Telegraph) and of “one of the most versatile, imaginative and radical sculptors of his generation” (The Independent). He will be remembered in other ways as well, such as by the “Warm amen” to The Independent obituary posted on the internet by Tony Crofts of Bristol, in which he recalls the sculptor’s personal generosity in a moving anecdote.

How many must have seconded that amen amongst the congregation who filled the church of Puig de Missa in Santa Eulalia for the service held on the morning of the eleventh of September. The fact that the key had taken an hour to turn up and it seemed at one point that proceedings might have to take place outside was neither surprising nor unappealing to those who knew Barry.

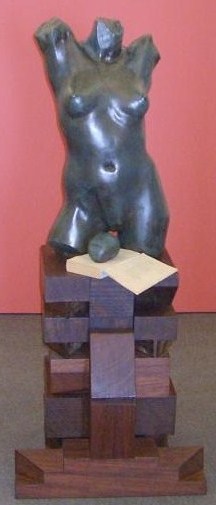

Eventually the doors were opened, and Jessica Sturgess, Barry’s partner, recited “Head of the Goddess in my Hands”, a poem by Antonio Colinas, which open on the page of The Penguin Book of Spanish Verse forms part of the work of the same name that can be found on permanent display at the Ibiza art museum. The date beneath the title, 654 BC, is the date of the foundation of the city of Ibiza; the goddess is Tanit, and the poem speaks of how the work of a sculptor endures beyond him.

Flan, one of Barry’s daughters by his first marriage to Sue, the other being Tara, recited, with feet bare, Jarry’s extraordinary description of God – “the tangential point between zero and infinity”. Later, in his sermon, the priest referred to this with some puzzlement, a detail Barry would have loved. The sculptor’s startlingly original collaboration with Hugh Cornwall of The Stranglers was also played: “Mantra of the Awoken Powers”, in which Barry, recorded down an answer phone, recites the poem by Sex W. Johnson against a background of electric guitars. More conventionally, there was a Eulogy by Enrique Juncosa, director of the Irish Museum of Modern Art, where a retrospective of Barry’s work was held in 2006, hymns and a reading from Ecclesiastes.

In the afternoon, family members, friends and fellow artists, including some of the leading figures in the world of European arts, gathered at the family house, Barry’s former studio on the road to San Carlos. Sandwiched between performances by two groups, various friends related anecdotes or recited pieces in tribute to Barry, ending most movingly with farewells from his children by Renata Widmann, Alfred and Annabelle.

To those who will miss seeing the sculptor on the island, complete with heavy corduroy jacket in the height of summer, pausing with a slightly distracted air to admire the ironwork on a grille or engage workmen in conversation, there are relics of his to be found. Apart from “Head of the Goddess”, there is the delicate Kourus horse he gave to Santa Eulalia and a wonderful ceramic that can be seen in the garden of a restaurant on the town’s promenade. More even than these, however, is the gratitude he left in the hearts of the many he helped and inspired with unstinting generosity. Barry was someone who enhanced both his surroundings and those around him, not just with works of endlessly-suggestive wit and beauty, but also by deeds dictated by the heart.

First published in IbizaNOW

head of the goddess in my hands

On a line with the prancing hare, placed between it and the hanging cloths executed in the seventies, is the remarkable golden torso of a woman and the almost featureless black head that gazes up at her, both mounted on rectangular wooden architect’s blocks. The head rests on a large paperback edition of The Penguin Book of Spanish Verse , opened at a poem entitled Head of the Goddess in my Hands, which bears beneath these words the date 654 B.C., the year of foundation of the city of Ibiza. The head in the poem is that of the Punic goddess Tanit, but the poem essentially treats of how the work of a sculptor endures beyond him:

On the morning of the exhibition the author of the poem, Antonio Colinas, one of the foremost poets working in Spain today, came and gave his blessing.

(Extract of a review for Ibiza Now of Barry Flanagan’s exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum of Ibiza in the summer of 1992, as quoted in the chronology of the catalogue for the 1993 retrospective in Madrid.)

A PATAPHYSICAL REDUCTION

Following is the ‘lost’ appendix that was intended for With Barry Flanagan. It is a continuation of the drinking scene in Palma de Mallorca on page 102 and features the actual appearance of Flanagan’s hero, the French playwright Alfred Jarry.

A STRANGE THING HAPPENED. Transported by a Tardis of Fernet Branca, I entered the Flanagan dimension. My relationship with space and time altered so all at once we had fast-forwarded to late afternoon and were grinning at complicities that would have made no sense to anyone else, except perhaps the shade of Alfred Jarry. As though summoned by this thought, a man entered the bar. He was extraordinarily thin and attired in bicycling gear – a tight sweater, short coat and old trousers tucked into socks that disappeared into dilapidated plimsolls. Strapped to his head, a pair of goggles compressed his long, centrally parted hair, which was very black and dripped with grease. He had a thin moustache, and his eyes were as dark and phosphorescent as a nighthawk’s.

‘Shitter!’ the newcomer exclaimed as he approached in what sounded like a distinctly malevolent tone.

Barry, however, did not seem at all put out by this. ‘What marvellous kit!’ he exclaimed.

‘Thought I’d put on my flea market best as the controls of my Time Machine indicated a ‘pataphysician was here. It seems I was mistaken.’

‘I am that ‘pataphysician,’ declared Barry grandly

‘Ah, you like pâté on your physics?

‘I prefer the patter of the quantum,’ responded Barry. ‘Now permit me to make a ‘pataphysical introduction…

The sculptor turned in my direction and a gasp escaped his Fernet-stained lips. The newcomer, however, did not bat either of his scimitar-like eyebrows as he exclaimed:

‘Bosse-de-Nage, companion of the good Doctor Faustroll! I thought you had died in the archipelago.’

‘Ha ha!’ I replied.

I wanted to express myself more eloquently, but ‘Ha’ seemed to be the only sound my mouth was capable of uttering. Furthermore, my arms were covered by thick yellowish-brown fur and instead of hands I now had paws.

‘A considerable improvement,’ murmured Barry.

Both he and the newcomer found my repetition of one syllable very succinct and looked at me expectantly as though waiting for more. I was, of course, by far the drunkest of the three, practically obliterated by the pungent and herbaceous spirit. Without further ceremony, the cyclist lowered himself onto a chair and slapped Barry on the knee.

‘I always like to pat a physician,’ he said.

‘I’m not a doctor though some might say my practice is prolific,’ retorted Barry who was drunker than anybody – completely paralytic, in fact.

‘My name is Alfred, but you may call me Jarry,’ declared the cyclist.

He was obviously much further gone than either of us. There seemed to be no rise and fall to his phrases: every syllable carried the same dead weight, even the silent ones. His intonation was like Holland, though he was not speaking Dutch.

‘The man needs a drink!’ cried Barry. ‘What will you be having, Monsieur Jarry?’

‘Absinthe makes the heart grow fonder.’

‘A prudent choice,’ said Barry.

‘Especially with an ether chaser.’

I went up to the bar and tried to order the former but finding no words forthcoming apart from the inevitable ‘Ha ha!’, I pointed to a bottle of Mari Mayans absinthe. Fortunately, it was the foremost of a drizzle of bottles that stood beneath a large mirror. The mirror bore the image of a dog-faced baboon. The depiction was incredibly lifelike. Strangest of all, as I lowered my arm so did the baboon. I opened my mouth, and the animal did too, revealing a row of yellow fangs. I was pondering what new optical marvel this was when I was struck by a disturbing suspicion. I winked and the saucy creature winked back: the baboon was I! This came as such a shock that I did not trouble the barman about the ether, which I timidly suspected might be against the law and was besides beyond my powers of mime. I returned to the table, bearing the glass and a small plastic bottle of water.

The newcomer peered at the drinks in disgust. ‘Where’s the ether?’ he demanded.

‘A regrettable omission,’ sighed Barry.

‘But I’ve been waiting an ethernity.’

‘Ha ha!’

Barry and the cyclist seemed to find this surpassingly droll, but nothing more ventured from my lips despite their patience. The cyclist peered suspiciously at the green liquid.

‘What’s this?’ he demanded.

‘Absinthe,’ said Barry.

‘So, where’s the fork balancing on the glass and the sugar cube cradled by it like Lautrec on a floozy’s knee?’

‘A regrettable lapse,’ Barry murmured.

‘This absinthe is pastiche!’

‘More like Pastis,’ said Barry. His tongue forked across his lip like a lizard’s.

‘Ha ha!’ I put in, a comment the other two found surprisingly enlightening. There was a long pause as they waited for me to elaborate but in this, they were disappointed.

Jarry sipped some of the liquid, spluttered, and spat what he had drunk onto the table. The barman, who was cleaning glasses, ignored this.

‘Maybe you should add water,’ suggested Barry.

‘Water! That odious poison, swimming with microbes and the oily scales of fornicating fish. A detestable liquid that gives birth to the drowned so they can bore us with their nautical anecdotes. Water would turn this impeccable and translucent liquor into milky sludge. I would sooner tar my face with gold leaf and honey. I tell you, Sir, this is not absinthe!’

If Jarry meant it was not the tipple of choice of Montmartre, he was right. Wormwood, the mind-altering plant that put absinthe on a par with peyote, had been subtracted from the beverage in accordance with a directive from Brussels. I wanted to explain this, but all that came out was a succinct ‘Ha ha!’

Jarry understood.

‘Trust those Belgians to fuck everything up,’ he said. ‘Get me a real drink, will you! Something to burn the throat and demolish the senses.’

I was by this time almost too drunk to stand, in terms of inebriation way beyond the other two, pie-eyed on the summit of Everest while they swayed among the foothills. I managed, however, to get to my feet and stagger to the bar where the barman supplied me with another bottle of Fernet Branca and a large brandy for Jarry.

‘That’s more like it,’ said the latter after he had drained more than half the contents of the glass in one long swallow. As far as being hammered, he had all the nails in him, being totally and utterly legless, whereas Barry and I had between us still one limb to stand on. The cyclist finished off the brandy and loudly demanded a refill.

‘Fancy a nibble?’ suggested Barry, who on a plastered scale of one to ten was definitely a nine, while the cyclist and I were all at sixes and sevens.

‘A nibble!’ Jarry hissed in a flat and deadly tone as though it were the most horrible word that had ever been invented. ‘Do you know what food does? It kills people. They eat all their lives and then they die! Munching, chewing and masticating destroy the teeth, whereas liquor irrigates the incisors. In a truly enlightened society avocados would be axed, beef banned, cheese censored, duck ditched, eggs excised, fudge forbidden, gherkins grounded, ham hexed, ichimi interdit, jam jettisoned, kumquats kiboshed, lamb liquidated, melon massacred, nuts nixed, offal off, peas proscribed, quail quelled, ratatouille rubbished, salami shredded, treacle terminated, ugli fruit usurped, veal vetoed, whelks whacked, xacuti x-ecuted, yogurt yucked, zucchini zapped!’

‘I think I get your drift, ‘ said Barry. ‘So, alcohol…’

‘Would be absolute! Aquavit advisable, beer binding, cognac compulsory, drambuie de rigeur, eggnog essential, Fino favoured, grappa glorified, hooch hailed, Inishowen imperative, Jägermeister judicious, Kahlua king, lager longed for, moonshine mandatory, Napoleon brandy necessary, ouzo obligatory, Pétrus paramount, Queen’s cocktails quenched, rum requisite, sangria stipulated, tequila treasured, Ultimate Margarita unavoidable, vermouth venerated, whisky welcomed, Xanthia x-pected, yashmak yearned for, zinfandel the zippiest! Just think of all the drinking time you lose because of lunch and dinner!’

The barman had stopped cleaning glasses and with a gleam in his eyes clamped a large cigar between his lips. Taking this as his signal, Jarry pulled a pistol out of his back pocket and fired. The shot embedded itself in the mirror behind the bar, which shattered. We hoped the barman’s fury at this might be mitigated by the fact that the bullet had lit his cigar.

‘Voilà!’ cried Jarry.

Far from being delighted however, the barman swore softly to himself, and, lifting the receiver of the telephone next to the cash register, began to rapidly dial.

‘Ha ha!’

‘You are completely right,’ agreed Barry. ‘It is time to reassemble elsewhere.’

Outside we found the sea had invaded Paseo de Born.

Ultramarine and turquoise hues danced in the ripples of foam that gently lapped our feet. As far as the eye could see there were islands of all shapes and sizes. Strangest of all, the sea between them seemed to be a different colour whichever way you looked. We soon discovered the reason for this as we waded in. This section of sea was as dark as wine and composed of the stuff. Inevitably, we took a few sips as we swam, enough for the cyclist to conclude it was Bordeaux – Pétrus, in fact – though he was not sure if it was the 1865 or 1866. Inspired by such a wine-dark sea, he began reciting the Odyssey in the original Greek.

The first island we came to was entirely made of crystal. It was a bit tricky for my companions to pull themselves onto the jagged shore, but with my long, dexterous arms I found this easy and of course my feet had a grip far superior to theirs. Crossing the surface, which refracted light like a prism, so our footfalls seemed to fall on rainbows, we came to a grove of tobacco trees. The ground beneath them was covered with butts but hanging like leaves from the branches of the first were clusters of cork-tipped Craven A. Jarry broke off a bunch, stuffed the seven cigarettes that composed it into his mouth and lit them by firing his revolver. After passing one to me and one to Barry, he inhaled his quota in greedy puffs and scanned the island in every direction.

Apart from the trees, there was only crystal. Whatever he was looking for remained elsewhere. I, however, became increasingly attached to the place, for finding the smoke unpleasant I broke my cigarette in half and began chewing the unlit portion whose pungent taste immediately made me crave more. I went into the glade and randomly plucked Three Castles and Capstan Full Strength from their respective trees, discovering after several hours of pleasant and dedicated chewing that Passing Clouds was infinitely superior.

Returning to the shore, we dived into the sea and made for the next island. This time we found ourselves swimming through warm sake. Barry, particularly, enjoyed this and began reminiscing about Japan. But Jarry complained the rice wine was not strong enough for his liking. On the next island there were mud volcanoes that made gurgling noises as they threw wet soil into the air – Blurp! Blurp! – which spattered our faces. Barry, of course, could not resist gathering up several handfuls, which he kneaded into a ball and then began modelling, giving quick-fire glances in Jarry’s direction as he did so.

‘Why does everyone want to reproduce my mug?’ demanded the latter, reciting a long list of artists he had posed for which included Rousseau, Gauguin and Aubrey Beardsley.

Barry, who had no time for namedropping, ignored this and continued to mould the clay, subjecting his model to frequent scrutiny as we walked. The word in fact does not describe our progress: neither does stroll, stray, saunter, sway or sidle. In fact, they staggered and then slid; I, of course being much more agile loped along on all fours. The passage of time and our exertions had put us on a par in terms of drunkenness: we were communards on the piss, entirely on an equal footing in terms of both tipsiness and the terrible thirst that made us anxiously scour the bizarre landscape for any sign of drink.

Fortunately, the next stretch of sea was to everybody’s taste consisting as it did of various single malts, sectioned by the current into zones. Jarry was at a bit of a loss at this point and let Barry be our guide as we immersed ourselves in Talisker, Bushmills, and then a Lagavulin whose peaty fumes made me almost lose consciousness. When not pondering vintages, Barry crooned pleasing Irish ballads.

We went on like this for many years, crossing oceans of rum, vodka, sloe gin, as well as the Straits of Guinness, seven seas of rye, and Mare Mort Subite, a dark sea brimming with mussels and the drowned, who floated by with happy smiles upon their faces. My favourite, though, was a lake of lager, whose blond surface was whipped into froth by wind. Sweet Afton trees, whose fruit I plucked and chewed, surrounded the lake. My companions found this a little plebeian, however. Barry going off to wallow in a pool of Connemara malt while Jarry stumbled on a cave of ether that was much to his liking. We travelled to hundreds of other islands in what seemed an infinite archipelago, each with unique fantastic features that are recorded elsewhere.[1] Finally, we reached one covered with rusting pyramids of mild steel and this Barry christened Cairo, informing us it had been made by a tribe of girder-welders. In the exact centre of the island, we found Jarry’s Time Machine.

The device consisted of a jointed, ebony structure that resembled a bicycle frame. At rest the machine sat on the circular rings of two gyrostats while the nickel ring of a third arched over the controls. The latter was made up of a lever with an ivory handle, which controlled the motor’s acceleration, and another on an articulated rod, which slowed the machine down. There were four ivory dials, which marked days, thousands of days, millions and hundreds of millions of days. Under the driver’s seat were the storage cells of the electric motor. Alongside these were the pedals that controlled them.

‘I was actually hoping to go back and see Jesus race the thieves,’ said Jarry, ‘but of course from the time machine’s perspective the past comes after the future, so you must do the former first, which explains why I dropped in on you. The machine works on the same principle as Breughel’s painting, The Massacre of the Innocents. You will have observed how the soldiers on the canvas batter down doors with the butts of their muskets in the streets of a Flemish town. This beneath a misty northern sky, as little like Herod’s Palestine as can be imagined. Yet make no bones about it: what you see is the massacre. Time not being matter, does not matter. Once you realize that you can set the controls for anywhen.’[2]

‘John Latham, who reduced everything to a dot, proposed time not place to be the quarry. Speaking of which, I wonder how the shark’s decaying,’ ventured Barry, putting the finishing touches to the clay head, which by now was the spitting image of the chrononaut. He turned and looked at me. ‘You should say thank you.’

I tried but all that came out was the inevitable ‘Ha ha!’ This time Barry and the cyclist did not wait for more. They had by now concluded that the frequency of my utterances was the key and shared an elaborate system of allotting voluminous meaning to the two syllables, depending when and how I said them. They nodded sagely to each other. The timing of my statement opened itself to no other interpretation than that of gratitude and farewell.

Jarry pulled down a side panel and hoisted himself onto the saddle. He began to pedal furiously, sliding the lever forward as he did so. The Time Machine started to vibrate and then lifted off the ground. Soon it was hovering just above our heads. Its pilot favoured us with a brusque nod and called out, ‘’Pataphysics is the science…’ as he and the Time Machine vanished.

‘Why do they always give you what you want and then take it away from you?’ demanded Barry.

‘Ha ha!’ I agreed.

[1] For a more detailed description of the archipelago see Exploits & Opinions of Dr Faustroll, ‘Pataphysician by Alfred Jarry.

[2] A description of the time machine along with instructions for its construction and use can be found in Jarry’s essay: ‘Practical Construction of the Time Machine’.

The Names of the Hare

An appreciation of Barry Flanagan

IN 1983, BARRY FLANAGAN AND SEAMUS HEANEY collaborated on an illustrated version of The Names of the Hare, the Irish poet’s rendition of the medieval poem. Beneath three characteristically graceful leaping hares, there is a roll call of the impish creature’s names, this being the only way the hunter could get the better of it. Sometimes during a conversation Barry would pause, strain forward and sniff the air, with his finely etched features and clumps of stubble the razor had missed, resembling the animal he had made his trademark. The identification went further: many of his hare-themed sculptures, prints and drawings have strong autobiographical overtones. The animal’s protean nature chimed with his.

and Ibiza resident Foxy, who

modelled as well for Francis Bacon.

The work is dedicated to Bacon

and was made on the

day of his death (15 July 1992)

Barry’s first hare was cast in November 1979. Up to then, the sculptor had occupied a worthy but straitened position amongst the avant-garde. He had grown to dislike the way “money punishes art” and had even resorted to making lino-printed “funds”, Flanagan money that could be redeemed against his estate upon his death, which he exchanged for jobs and materials. He had a wife, two young daughters to raise, and a CV made up of casual labouring jobs and shows that had caused hardly a stir. Riding a white bicycle around a gallery while obliging visitors cut Yoko Ono’s clothes off with scissors did not help with the rent. Glimpsing a hare on the Sussex Downs, buying a dead one from the butcher and bringing it to the foundry to model, allowed Barry to leap away from pure conceptual art and embrace the “concept of trade”. He attended business courses and took to wearing a tradesman’s cloth cap and a bespoke suit with sketchbook pockets, a type of costume he would persist with when living on Ibiza, whatever the temperature. “When out of the garret one no longer works alone but finds a place in the scheme of things,” he remarked.

Mercurial, mythological, magical, the hare was an immediate success and Texan billionaires, French wine producers and Japanese hoteliers jostled to buy one. Barry was photographed by Snowdon for Vogue Magazine and represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1982. He had arrived yet was still driven by the prankster spirit that had inspired him to place a turd-shaped stone to the rear of Henry Moore’s Sheep Piece at the Silver Jubilee Exhibition in Battersea Park. The hare, after all, was ‘the wild one, the skipper, the hug-the-ground, the lurker, the race-the-wind, the skiver’. Moreover, it had pedigree in the same out-there territory as Barry’s initial explorations, consider Joseph Beuys’s 1965 performance art piece How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, in which the German artist spent three hours cradling the dead animal in his arms as he whispered the meaning of his drawings to it, with honey and gold dust dripping from his head. It is probably not a coincidence (of which Barry was an adherent of the “no such thing” school) that the two artists – mavericks and shamans both – occupied adjoining rooms in the early days of Tate Modern.

Poetry not sculpture was Barry’s first love. He would describe himself as ‘the poet of the building site’ while a labourer. From the basement of Better Books in the Charing Cross Road, where the owner Bob Cobbing had installed a typewriter, Barry produced a weekly magazine called Silãns. This was 1964 and Barry was studying at St Martin’s School of Art where some of the fifty cyclostyled copies were given away every Monday morning. The rest were placed in the bookshop. He was drawn to concrete verse, attending the famous poetry festival at the Albert Hall featuring Allen Ginsberg in 1965 and delivered a silent lip poem in the Second International Exhibition of Experimental Poetry in the same year. He was delighted when he found a way to rhyme ‘cider’ with ‘crazy’, a feat very much inspired by the former. Concrete poetry served as well to provide titles for his fledgling sculptural work. The group of felt-stuffed pieces confined within a circle, which have the absurd, brooding appearance of characters from a play by Barry’s hero, the French writer and founder of Pataphysics, Alfred Jarry, is titled aaing i gni aa, first exhibited in Better Books and subsequently bought by the Tate. Another title, ‘Four Casb 2 ‘67’, seems to be drawn from the same enigmatic territory but is a matter-of-fact description of the materials employed and date of use: four canvas sandbags, number two, 1967.

I first met the sculptor on Ibiza in 1987. He had just moved to what he would describe as “this haunted, blessed place”. In his dusty green cord jacket and worn baggy denims, I took him to be another scruffy irregular of the artists’ brigade that caroused and occasionally put paint to canvas or pen to paper, drawn to the island by its climate, tolerant locals and cheapness. It took me a while to realize Barry had an international reputation and significant wealth. While living on the island, apart from properties in London and a room reserved at the Chelsea Hotel in New York, he would rent flats or buy houses in any place his career happened to collide with, such as Barcelona, Amsterdam or Dublin. He also acquired or rented several properties on Ibiza, even selling and then buying back his main house on the island. The beneficiary of the last shared the same first name as me and several people congratulated me on the windfall. Coming from a theatrical family, Barry was nomadic by nature, but instead of pitching a tent, he would acquire property wherever he happened to be. This was necessary for him he said and tallied with his sense of place.

I would frequently visit him in his rambling house. Wearing loose-fitting Japanese robes or a wide-sleeved dressing gown, he would mull over titles for the pyramid-shaped works in mild steel, which looked to my untutored eye like hulks rusting amidst the overgrown weeds of the garden, or ask me to help him arrange a set of architect’s blocks, a nearly featureless black head, and a torso modelled on his wife Renate that had originally been a shop-window mannequin. He never seemed to find the right arrangement for the group. Most of the time, however, he seemed not to do much at all. It was beyond me how he had become so successful. I wondered if the island was turning him into a lotus eater. An old friend of his in London, however, told me this was always how Barry operated. Not for him a 9-to-5. He could lie fallow for considerable periods but was very productive when he toiled. Drinking a lot, mainly whisky, he made it plain he was a “pissed artist” not a “piss artist”.

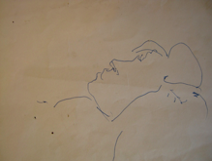

A conversation with Barry was often a daunting, multi-dimensional mind-game. “When I lob a ball, I expect a decent return …” he would say. His analogies were frequently drawn from tennis or cricket. Certain key terms pervaded his speech: “civility”, “address” (the verb), “as a student”, “practice”, “trade”, and he could be just as sculptural with language as he was with bronze. “Don’t pay homage to a dead weight!” he once admonished me, in what I took to be a reference to an exacting muse. It was useless to engage him in small talk. An enquiry as to his health or a comment about the weather would be met by anecdotes concerning the experimental art scene of the 1960s. Whether you were familiar or not with the people he mentioned did not seem to matter. He delighted in wordplays. There is a drawing he made in the 1970s called Keeping ones own tracts open, which consists of that phrase towards the bottom of the sheet with the same words written backwards beneath it. The sheet is empty. Barry was very much keeping his tracks open. The joke is ‘tracts’, the most prescribed of literary forms.

He used the walls of his Ibizan house as a notebook, on which he scribbled haikus and aphorisms in pencil or red-brown ink. Some were droll: is it my fault I chose life over employment? A rejoinder he had made to a belligerent tax inspector. Others illustrated his guiding principles: true judgment resides in the heart. Others, still, such as the hues of the ripple, crystallized his multi-faceted approach. Once he asked me to arrange for a photographer to take shots of some birds he had drawn on the wall. This subsequently became an etching.

One day he gave me a shoebox with five clay pots in it and told me to take it to the museum. There were two to choose from, archaeology or contemporary art. His pinch pots, as they were called, had an unfinished prehistoric look so I spent half an hour of mutual bewilderment with the director of the former. More fruitful was a connection I established a short while later with the art museum, which led to Barry being offered a show in the sixteenth-century building’s cellar, which had originally housed the gunpowder and animal feed of the city garrison. The first meeting was at his house, an exceptionally warm spring day. The sculptor made a blazing fire and with great courtliness drew the sofa the museum director was sitting on as close as possible up to it. The elements mattered not a jot when it came to hospitality.

Compared to Barry’s usual stamping grounds Ibiza was a very provincial gig, but he took to the challenge with gusto, filling the space with exquisite drawings, hangings, and mild steel pieces, which he had the brilliant idea of ringing with salt from the pans at Salinas. He recreated a work called Light on Light on Sacks, first shown at the Hayward Gallery in 1969. This consisted of a heap of thirty hemp and flaxen sacks stuffed with carob beans acquired, on a sale or return basis, from a puzzled farmer in San Carlos. A projector shone a square of light onto them. After the exhibition had been extended by popular demand, they attracted rats that ripped open the sacks and feasted on their contents. Barry went AWOL a couple of times the week of the hang and it seemed touch and go whether he would be there for the opening. The day arrived and a morning of fruitless searching ended when we found him asleep on a couch in the basement gallery surrounded by his treasures.

During the hang, he finally worked out the proper arrangement for the architect’s blocks and placed the now gilded torso on them with the round black head gazing up at the belly. Beneath the round black head Barry put a photocopy of a poem I had come across in The Penguin Book of Spanish Verse called Head of the Goddess in my Hands, which treated of the way sculpture endures beyond the life of its creator, I had been struck by the fact that the date beneath the title, 654 BC, was that of the foundation of the city of Ibiza by the Phoenicians and discovered the goddess of the title was the island’s presiding deity, Tanit. The poem’s author Antonio Colinas lived on the island and came to the museum. He was happy for the poem to be used but said a photocopy would destroy the exhibition, so we substituted the book, opened at the relevant page, instead.

Fortunately for Colinas, Barry did not use literature in sculpture in quite the same way he had with John Latham in the Sixties. Latham was a part-time tutor at St Martin’s, which at that time had a tradition of inviting radical visiting lecturers, such as Alexander Trocchi and R D Laing. Another was the American Clement Greenberg author of Art and Culture, which argued that the best avant-garde art was American and dismissed British Art as ‘too tasteful’. Bridling at this and the polemical tone of the book in general, Latham, Barry and a group of St Martin’s students organized an event called ‘Chew and Still’, in which they chewed a third of the book’s pages. The result was spat into a small glass flask, where it was submerged in sulphuric acid until the solution turned to sugar. Yeast was added, the mixture left to ferment, and then poured into a glass vial Latham labelled ‘the essence of Greenberg’. Unfortunately, Latham had borrowed the book from the college library and was sacked for his efforts. The Museum of Modern Art in New York later acquired the piece, now called Art and Culture. Barry donated Head of the Goddess in My Hands to the Ibiza Museum of Contemporary Art, and it is on permanent display, among the most romantic and lyrical of his works.

In September 1992, we took the show to Palma and while there hired a car to visit the celebrated Spanish artist, Miquel Barceló. Barceló spent four months of the year at his home in the north of the island, dividing the rest between Paris and Mali. Barry was driving, and I asked him why he was keeping his eyes so determinedly fixed on the road and ignoring the terrain. He explained he disliked being dwarfed by mountains. We hit on the term “invertigo” to describe this. Later this chimed with something his mother Monica told me. By being born in 1941, Barry had spent the first few years of his life effectively as an only child, his two older brothers and sister evacuees in North America. Their return at the war’s end and the attendant decline in attention came as a terrible shock. In some senses, the sculptor’s art was a battle to be heard. Nothing riled him more than to be ignored or made to feel underestimated. As we continued our journey up the rugged west coast, Barry remarked there was so much stone a sculptor could get indigestion.

In 1994 I upped sticks from Ibiza and returned to England. I was like the fabled Spanish general who had not a clue where he was going but wherever it was, he would lose his way. Barry chided himself sometimes for neglecting old friends, but this was never my experience. He knew I needed to connect with my surroundings so underwrote a tour of quarries. I did this in the company of an old friend, the actor Oengus Macnamara. We visited Doulting, the source of the stone for Wells Cathedral, and Ham Hill with its Saxon forts. Gradually, it dawned on me that there was a subtext. Cracking the code of Barry’s telephoned instructions led us to Beer in Devon in pursuit of Fred Newton, in youth an apprentice banker mason at the local quarry, who had given Barry a job in 1959. We were directed to Banbury, where Barry had undergone a brief apprenticeship as a dental technician with the exquisitely named Mister Mold, and to Oxford, where in 1975 he had blocked out one of Michael Black’s Philosophers for the Sheldonian Theatre while working as a stonemason. My travels resulted in a report on stone and quarries called No Stone Unturned, which I presented to him in the Groucho Club. Afterwards, I committed the unpardonable sin of sitting on Ian Board’s chair at the Colony Club, which I compounded by falling off it.

What baffled me most in England was why I had abandoned my life of pleasant hedonism on Ibiza and come back. A sort of answer was provided when I met a profoundly deaf fourteen-year-old girl at a reunion of old friends who turned out to be my daughter. She had a flair for art. A couple of years later it became necessary to fund her studies. I appealed to Barry. In response, I received a letter consisting of one phrase: Long a moving line. On one level, the words seemed to refer to the emotion produced by my letter. But another interpretation was the line was my family which, with this discovery of a daughter, was in moving on. Barry told the college he wished to fund another student should my daughter not complete her studies. There is an abundance of such stories. One thing that distinguishes the hare from the rabbit is its heart, which weighs up to 1.8% of total body weight compared to the latter’s 0.3%. ‘Great-hearted, life enricher, selfless giver,’ words that fit Barry like a glove.

For more see my book, With Barry Flanagan – Travels through Spain and Time (The Lilliput Press)

Made at the tip of Africa. ©