Richard C McNeff

Author

Contents of This Page

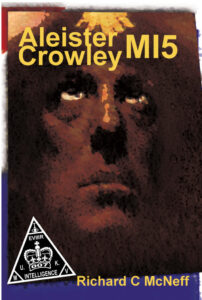

1) Aleister Crowley MI5 plot summary & reviews

2) Aleister Crowley MI5: the story of the book (Fortean Times)

3) Crowley and Huxley: A Trip in Berlin? (FT article)

4) The Compleat Beast (FT review)

5) The Beast and MI5 (FT article)

6) Secret Agent 666 (FT review)

7) The Beast in Britain (FT review of Gary Lachman’s map)

8) The Beast Goes On: Aleister Crowley & Rock

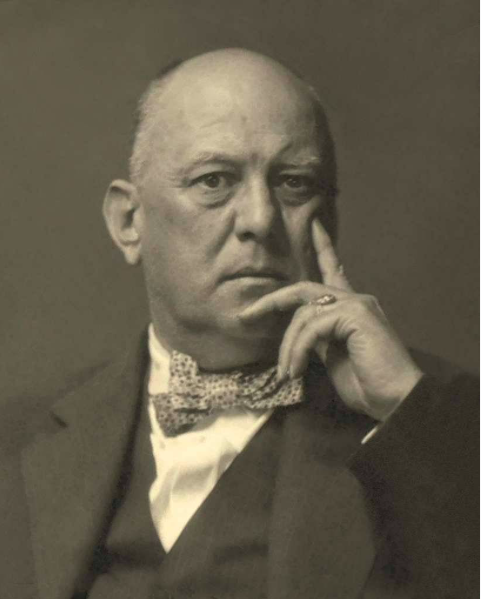

Editions (originally titled Sybarite among the Shadows)

“Occasionally, there were visions: the Algerian desert with its fountain of stars, the chain by which his master led him chafing his neck as they trudged across the sand; the uncanny light dancing with shadow in the Paris hotel room where they had invoked Jupiter (the face of the God, awesome and unbearable). Nothing remarkable would ever happen again. He had become the curator of his youth.”

What if the Beast returned and you were not sure if he were the best or worst thing that had ever happened to you?

A shocking encounter with Aleister Crowley in a Soho pub launches Dylan Thomas on an adventure whose first stop is the opening of the Surrealist Exhibition on June 11, 1936. With the Welsh poet is his first editor Victor Neuburg, the Beast’s lapsed apprentice. In the bohemian fleshpots of Fitzrovia and Soho they connect with such luminaries of the period as Nina Hamnett, Augustus John, Tom Driberg, King Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson, as well as Crowley himself. Neuburg confronts the terrifying magick of his youth and something even more menacing — a Crowley orchestrated MI5 plot to avert the abdication. Aleister Crowley MI5 is an exhilarating work of fiction with highly researched fact at its core.

‘McNeff’s novel is so different from anything else you’d normally find on a bookshelf that it should perhaps be a compulsory purchase.’ – The Independent on Sunday

‘Probably the finest modern novel featuring Aleister Crowley.’ – lashtal.com

‘Brilliantly researched, this is an astonishing read, a 24-hour snapshot of the seedy underground life of artists, poets, prostitutes, spies, and royalty of mid-Thirties London, all revolving around the fading powerhouse that was the Great Beast.’ – Fortean Times

‘…highly entertaining imagining of what Crowley might have got up to.’ – Cathi Unsworth (Season of the Witch: The Book of Goth)

‘A very clever idea, fleshed out with wit and style and an excellent sense of the times.’ – Silverstar’

‘Exhilarating, extravagant, irresistible, a continuous cocktail of truth and fiction, this novel is an extraordinary portrait of 1930s London; a daring odyssey of pubs, prostitutes and occult sciences, a poetic art deco thriller, seen through the bluish haze of cigarettes and opium, in a nightclub that remained open until dawn.’ – Robinson –La Repubblica

‘A swaggering romp of a novel. Plot by Buchan; characters by Beardsley, setting Art Deco – difficult to better that.’ – Wormwood

‘Full of fascinating nuggets, Neuburg’s crisis of identity with AC is very well observed.’ – Snoo Wilson, (author of I, Crowley)

‘This is an unusual and intriguing novel and an entertaining foray into an earlier, stranger England.’ – compulsivereader.com

‘Here in a highly researched story … Crowley is himself in all his occult and charismatic glory – a manipulative, overbearing, bizarre yet compelling character. Fiction could hardly have invented him: he is a gift of character for any novelist and Richard C McNeff has accepted him, unwrapped the parcel and given him his head.’ – Martin Booth, (author of A Magick Life: A Biography of Aleister Crowley)

‘…a tour de force of historical fiction, blending fact and fantasy into a seamless and exhilarating narrative…a must-read for anyone interested in the occult or early twentieth-century history.’ – Marco Visconti (author of The Aleister Crowley Manual)

‘We find ourselves in the presence of a novel of great fascination…McNeff reconstructs the climate of those days with gusto…involving astonishing encounters, including the one with Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson.’ – Il Manifesto

‘An irresistible intrigue’ Vanity Fair Italy

THE STORY OF ACMI5

In 1977 International Times published my short story ‘Sybarite among the Shadows’. I based the story on an anecdote I found in Sexuality, Magic and Perversion by Francis King, which relates how Aldous Huxley was given his first mescaline trip by Aleister Crowley in Berlin in the Thirties. The thought of two such divergent characters in such a setting intrigued me. For added spice, I added some atmospherics concerning the influence of the German branch of Crowley’s magical order, the OTO, on the Nazis – such speculations being very much in vogue at the time. Victor Neuburg, poet and disciple of the Beast, acted as narrator.

The story caused something of a stir and the American magazine High Times contacted me with a view to publishing it. They assumed I was in possession of the secret diaries of Victor Neuburg. Sadly, I had to disabuse them of this notion. Fourteen years later, I found an anthology called Rapid Eye at the big Virgin store on New Oxford Street. The famous photo of Aldous Huxley parting a torn hanging, symbolising the the doors of perception, was on the cover. The blurb promised transgressive writing. Wondering why I never featured in such anthologies, I leafed through pieces by Derek Jarman and William Burroughs until I came across my name misspelled at the top of a page and the Crowley/Huxley story beneath it. In fairness to the editor, the late Simon Dwyer, I was then living abroad and he had tried to contact me.

No such attempt was made in Russia where it was translated and posted online a further decade on. Pan’s Asylum Camp, a website that describes the development of Thelema in Russia, lists the story as part of the collected works of Crowley, published in 1997. According to the website, many Russian readers took the story to be true as did Micheal Howard — no relation I am assuming to the former leader of the Conservative Party, though the politician’s Transylvanian ancestry might suggest otherwise. In The Occult Conspiracy Howard relates how “Crowley had confided to the writer Aldous Huxley in 1938 when they met in Berlin that Hitler was a practising occultist. He also claimed that the OTO had helped the Nazis to gain power”. Such a notion persists. A recent coffee-table book, The Nazis and the Occult by Paul Roland, assumes the story to be a factual account written by Neuburg, quotes extensively from it, and uses one throwaway line attributed to Crowley to justify the claim that Hitler also used mescaline.

Crowley and Huxley did indeed spend time together in Berlin and Crowley used mescaline liberally for many years, famously spiking the audience during the Rites of Eleusis in 1910. Apart from King’s aside, however, evidence that he introduced Huxley to what was then called Anhalonium Lewinii is sketchy. Nevertheless, through the alchemy of other writers, it seems my faction has transmuted into fact.

The idea of using Neuburg as the narrator of a longer work persisted. At first, I considered portraying the extraordinary events of his eight-year association with Crowley – the invocation of John Dee’s Angels of the Aethyrs at Bou Saada, the Paris Working etc. Then an approach from another angle sprang to mind: a reunion in the Thirties with Dylan Thomas as the link.

As poetry editor of the Sunday Referee, Neuburg had discovered the Welsh bard. Jean Overton Fuller’s The Magical Dilemma of Victor Neuburg was the primary source for this but there were others, most of whom she lists in the excellent bibliography at the back of her book. There is a detailed portrait, for example, of both Crowley and Neuburg in Arthur Calder-Marshall’s long out of print The Magic of my Youth. Here Vicky appears without a halo: his eccentricity has edge. Rupert Croft-Cooke devotes a chapter to him in Glittering Pastures. In Laughing Torso, the memoirs of the painter Nina Hamnett, which Crowley sued her over, there is the story of the actor Ione de Forest and the bizarre ménage she formed with Vicky and the Beast, which culminated in her suicide. Hamnett does not name Neuburg but refers to him as the Poet throughout.

In his limericks, letters and The Confessions, Crowley is predictably scathing about Neuburg, the disciple who reneged. More surprising is Dylan’s attitude. In Fuller’s book, uncharacteristically meek and sober, he gratefully laps up his mentor’s wisdom. In The Collected Letters, by contrast, he is full of scorn for “the Creative Lifers” as he dubs Vicky and his circle. “The creature himself – I must tell you one day if I haven’t told you before how Aleister Crowley turned Vicky into a camel – is a nineteenth-century crank with mental gangrene, lousier than ever before, a product of a Jewish nuts-factory, an Oscar tamed.” (To A.E. Trick – December 1934).

There is much more in this vein to several correspondents. Dylan loathes Vicky’s view of poetry, in which all must be sweetness and light. “Word tinkling” he calls it. Neuburg told Fuller that he had read some of Crowley’s poems to Dylan. He did not like them. Neuburg’s book of poems, The Triumph of Pan, is still in print but likewise is of a style that has little appeal to modern tastes.

Originally published with the same title as the short story, Aleister Crowley MI5 takes place during the course of June 11th, 1936, the date of the opening of the Surrealist Exhibition in London. It begins with a flustered Dylan visiting Neuburg at his home in Swiss Cottage. In a Soho pub the previous evening a sinister stranger had mimicked Dylan’s doodling. The stranger then approached and revealed he had drawn the same picture as the poet before introducing himself as the Beast.

The story of Dylan, Crowley, and the doodle is not my invention. Constantine Fitzgibbon relates the incident in his Life of Dylan Thomas. In fact, after the publication of the novel in 2004 I heard from Geraldine Baskin of Atlantis Books someone who was actually present and could corroborate the incident firsthand. I found several references to Crowley in Dylan’s letters. Both were integral members of a bohemian scene that flourished in Fitzrovia and Soho and had several friends in common, including the painter Augustus John. Just as Somerset Maugham, Anthony Powell and Ian Fleming had done so, Dylan even based a character on the Beast. In The Death of the King’s Canary, a posthumously published satire the Welshman composed with John Davenport, there is a sinister marijuana-smoking magician called Great Raven. The code is not difficult to crack. Nina Hamnett appears as Sylvia Bacon – to his friends, the Beast was “Crow”.

Dylan and Neuburg embark on an adventure, whose settings include the Surrealist Exhibition, the Café Royal, the Fitzroy Tavern, and the Gargoyle Club. They encounter Augustus John, Tom Driberg, gossip-columnist, spy , Labour MP and at one time Crowley’s magical heir, along with other well-known members of the London demi-monde, such as “the tiger woman” Betty May. The narrative connects each to Crowley, as did life.

Reunited with the Beast, Neuburg becomes involved in a plot hatched by Crowley and MI5 to avert the Abdication. There is a growing abundance of evidence linking Crowley to the Secret Service, explored most recently in Secret Agent 666 by Richard B.Spence. Spence also goes into some detail about the Beast’s use of mescaline as a kind of truth drug, anticipating the CIA in this respect. In addition, Neuburg and Crowley employ again the magic they have used in an attempt to exorcise the consequences of their earlier Workings, which have played havoc with Vicky’s life.

According to Fuller, Neuburg, a formidable seer, was put in a triangle in 1910 and possessed by the god Mars. He predicted there would be two wars within the next five years, one centred on Turkey and the other on Germany. The result would be the destruction of both nations. My novel contends that Mars still inhabits Neuburg: the book opens with him in an armchair undergoing a vision of war. In 2002, Marc Aitken made a short film called Do Angels Cut Themselves Shaving – a quote from Magick without Tears. This commences with Neuburg in his armchair also experiencing martial visions. It ends with a reunion with Crowley. Marc and I were working completely independently of each other. Coincidence, some might say. Yet if the hypotheses of magic hold true there is a numinous architecture, which we glimpse, and sense we are here more fully to behold.

As a somewhat tongue-in-cheek illustration of this, I am grateful to the eagle-eyed contributor to Iamaphoney, a Beatles blogspot, who recently spotted that if you draw a line from the photo of Crowley to that of Lennon on the cover of Sergeant Pepper, it intersects first Huxley and then Dylan Thomas, mirroring my short story and novel. The sixties ley line then crosses Tom Mix’s hat, behind which reputedly Hitler is lurking alongside Oscar Wilde. Cyril Connolly of course memorably described Crowley, “the Picasso of the occult”, as the missing link between the two.

For further information see: www.mandrake.uk.net/richardmcneff

THE COMPLEAT BEAST

(Fortean Times)

The Weiser Concise Guide To Aleister Crowley by Richard Kaczynski Ph.D – edited by James Wasserman (Weiser Books – ISBN: 978-1-57863-456-9 – U.S. $ 12.95) 128 pages

In April 1946, an eccentric Christian priest called F.H. Amphlett Micklewright wrote an article for The Occult Review [1], which praised Aleister Crowley as a poet and occultist. Delighted, its subject, who had little more than a year to live and was dwelling in obscurity on the south coast, wrote, “What we want above all is to be taken seriously by serious people.” The Weiser Concise Guide makes a worthy contribution to this ambition.

Richard Kaczynski, the author, is a “high-ranking” member of the OTO and The Guide bears all the hallmarks of an authorised version. According to James Wasserman, the editor, Kaczynski was given the task on condition that “the work be vetted and approved by a carefully chosen board of Thelemic scholars and magicians”. Despite such strictures, dogma rarely intrudes into Kaczynski’s prose, which provides a lucid and sincere exposition of its subject. He has an exhaustive knowledge and rightly highlights Crowley’s more remarkable productions, such as Magick in Theory and Practice and the Thoth Tarot. Until the inevitable appearance ofThelema: An Idiot’s Guide this will probably remain the best place for the novice to start.

Kaczynski is also the author of Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley. Around the time of its publication I attended a lecture he gave in London, in which he focused on the Beast’s versatility. The life, which opens The Guide, adopts a similar perspective by providing glimpses of Crowley as poet, mountaineer, magician etc. within a chronological framework. Given its brevity and the complexity of its subject, it does so with style.

The description of magical and mystical societies in Part I underlines the intricacy of Crowley’s system and how arduous its pursuit can be. In 1945, for example, Crowley examined his student Kenneth Grant on the correspondence between different forms of Buddhism and those of Christianity, the conflicting meanings of the number 65, and asked him to describe a woman according to strict astrological criteria. To attain different grades it is necessary to master such diverse disciplines as yoga, Egyptian mythology, eastern and western mysticism and meditation within organisations as ceremonially and hierarchically labyrinthine as the Masonic lodges they resemble. Crowley’s system is not intended for the easily hoodwinked who flock to join sects. His Qabalah is not the red string-around-the wrist variety.

Kaczynski encourages his readers to perform the magical exercises described in Part II on the grounds that “magick cannot be understood by simply reading about it”. The exercises include keeping a magical record, solar adoration and banishing rituals. One of Crowley’s more controversial practices was to prohibit students pronouncing a common word, such as “I”. Infractions were punished by cutting the forearm with a razor. Kaczynski is gentler and confides that modern students have reported good results from snapping a thick rubber band kept on the wrist. Part II closes with a section on sex magick. Anyone hoping to “do” this at home will be frustrated. The instructions are Crowley’s own and use such ciphers as “the Magick Rood” and “mystic rose”. The secret is kept: its disclosure confined to the highest grades, as Kaczynski himself makes clear. The book concludes with two appendices, both by Crowley and both dealing with the governing of his magical orders – a reminder that The Guide prioritises “proper channels”.

Crowley divided his writings into different classes, which The Guide delineates. Class A consists of inspired writings in which not a comma can be changed. Pre-eminent among these is The Book of the Law, which includes a blood-curdling attack on the established religions of the day. Kaczynski informs us that this “militates against the idea of a New Age multicultural approach in Thelema”. In a world wracked by the clash of fundamentalisms this seems a little ominous. Crowley, after all, was a pagan, a poet and bohemian prankster who believed an idea must contain its own contradiction in order to be true. In Eleusis, produced in 1910, he listed a host of unorthodox callings, such as “a Shaker, or a camp-meeting homunclus”, that were far preferable to being “a smug Evangelical banker’s clerk”. In this, the pariah of his times displays extraordinary clairvoyance by targeting the bogeyman of ours. I refer, of course, to the banker.

[1] “Aleister Crowley, Poet and Occultist” The Occult Review Vol.LXXII No 2, April 1945, pp 41-46 – reprinted by the Fine Madness Society.

THE BEAST AND MI5

At Aleister Crowley’s cremation in Brighton in 1947, the uproar sparked by the recitation of his sexually explicit “Hymn to Pan” was the last scandal of the magician’s life. It seemed the Great Beast 666 was doomed to join the roster of forgotten English eccentrics. Instead, fanned by John Symond’s biography, The Great Beast, interest simmered through the Fifties. Then, in the Sixties, the Master Therion burst into the public arena on the cover of Sergeant Pepper – included as one of the people the Beatles liked. His experiments with sex and drugs, his fascination with the occult and the East, dovetailed with those of the time. Since then his influence has grown. Due to the number of dedicated websites, The Observer describes him as the “Demon of the Internet”. In 2003, he came number 76 in the BBC poll of famous Britons. His work populates mainstream as well as New Age bookshops. With his shaven head and phallic forelock, outrageous costume and staring eyes, Crowley is a figure for our times and would not seem out of place on Camden High Street.

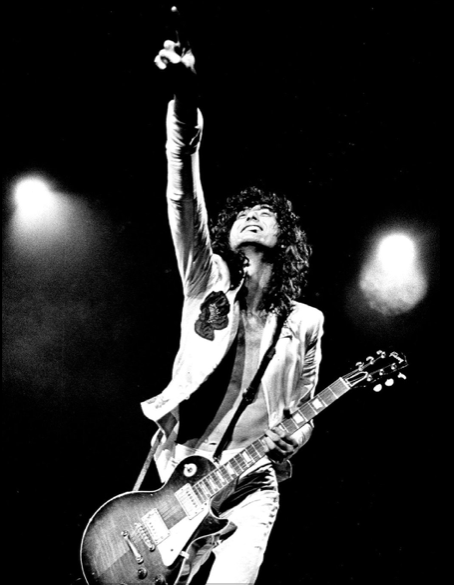

His life intersected with those of more celebrated artists: Rodin, Yeats, Augustus John, Aldous Huxley. Several writers, including Somerset Maugham, Anthony Powell and M.R.James, based characters on him. His influence is present in the music of Bowie, Ozzy Osbourne and Jimmy Page. There is another strain in his life, however, which has received little attention up to now: his connection with the Secret Service.

The link between magic and espionage has a long tradition. John Dee, the renaissance magician, was a member of the Elizabethan Secret Service – Ian Fleming appropriated his cipher 007 for James Bond. Dee integrated Enochian, his angelic language, into his spying, where it served as a code. More recently, at the tail end of the Nineties, the head of French Intelligence astounded journalists with the news that the onset of the Age of Aquarius would produce much turbulence. Papers remain classified; those released contain blacked out passages. Yet when one considers Crowley’s openly flaunted bisexuality and drug taking, the lurid practices at the Abbey of Thelema he established on Sicily, which led the yellow press to brand him ‘The Wickedest Man in Europe’, the suspicion grows that he enjoyed some kind of protection, further than that afforded by his Guardian Angel Aiwass. Expelled from Italy then France, the author of Diary of a Drug Fiend was never arrested on British soil. In Tiger Woman, Betty May accused him of the ritual murder of Raoul Loveday, her husband – he was never tried. Misunderstanding his sexual metaphors, Nina Hamnett, hinted at cannibalism and the sacrifice of infants in her Laughing Torso – he was never imprisoned.

Crowley’s first known links to the Secret Service occurred during the Great War. At the outbreak, he fled to America and became a regular contributor to a periodical called the Fatherland, which printed the crudest German propaganda. He made a speech at the Statue of Liberty execrating his homeland, tore up an envelope, which he claimed contained his passport, and unfurled the flag of the Irish Republic. The New York Times reported all of this. MacAleister, as he now described himself, then edited the rabid, German-funded International, whose pages he filled with anti-British invective, magick and the location of a detested aunt’s house in Addiscombe, which he hoped Count Zeppelin would bomb. Yet on his return to England, he received not a word of reproach, apart from a trouncing in John Bull. Charles Parnell was hanged for his collaboration with the Germans in the First War; the same happened to William “Lord Haw Haw” Joyce at the end of the Second. In 1919, Scotland Yard launched an investigation into Crowley, which was aborted on the instructions of the Service.

In later years, Crowley claimed he had been working for both British and American Naval Intelligence with a brief to make German propaganda ludicrous – there is evidence to support this, apart from his over-the-top panegyrics to the Kaiser. The Service certainly paid him to spy on Gerald Hamilton when they shared a flat in Berlin in the early Thirties. Hamilton, Christopher Isherwood’s Mr Norris, a lover of boys, wine and good food, was simultaneously a Monarchist and fervent supporter of Irish Republicanism. He was the only Englishman interned in both world wars and had close links with the Abwehr.

Throughout his career, Crowley exerted a fatal attraction on Oxbridge undergraduates. Communism and Fascism were not the only landmarks on the horizon. There was the tower Magick and the mage himself, Mr Crowley, sitting wreathed in smoke at the top. Much, in fact, like Great Raven, the caricature Dylan Thomas and John Davenport drew of him in their satire on contemporaries, the Death of the King’s Canary. The most prominent of Crowley’s varsity fans was Tom Driberg, the first William Hickey, the Daily Express’s gossip columnist, subsequently a maverick Labour M.P. and member of the National Executive. Driberg wrote an oath of loyalty to the Beast on parchment. Crowley took to describing him as his ‘magical son’. Driberg was also an MI5 spy. He infiltrated the Communist Party of Great Britain only to have his cover blown by his colleague Anthony Blunt. MI5 realised they housed a traitor but their report, ‘The Cominterm is not dead’, was binned with famous consequences.

Driberg’s spymaster was Maxwell Knight, who ran B5b, a section of MI5 so secret that many in the Service knew nothing of it. B5b’s remit was enemy subversion. In 1938, it cracked the Soviet spy ring at the Woolwich Arsenal. Knight shared his headquarters, a flat in Dolphin Square, with a baboon and tame bear he took for strolls along the King’s Road. In the Fifties, he started a second career and became a well-known broadcaster on wild life. Twenty years before this, along with Dennis Wheatley, he studied under Crowley. Reputedly, he possessed a mesmerising personality, which attracted two wives, though he was devoutly homosexual. Partly because of this, his first wife committed suicide. The other motive was given as Knight’s entanglement with Crowley. Throughout the Thirties, B5b increasingly focused on Nazi subversion, and the fifth column in the Establishment. It infiltrated the Anglo-German Fellowship and crypto-fascist Link, as well as monitoring the activities of Wallis Simpson. This partially explains the Abdication.

Crowley’s reaction to Nazism was more ambivalent. The world was on the brink of a new Aeon. The age of Horus was to be merciless, with no quarter for the infirm or afflicted. In many ways, the Nazis fitted the bill. Hitler was patently the head of a magical order with uniform, symbol and book, though, in the Beast’s opinion, Mein Kampf was not a patch on his own the Book of the Law. A German follower duly delivered a copy of the latter to the Fuehrer. Crowley claimed Hitler had filched a lot from him when the Table Talks appeared. Yet the Beast had no truck with the “Black Brothers” racial theories, and the German crackdown on esoteric organisations, including his own OTO in 1935, alarmed him. When war came, he published a Pantacle for victory and claimed to be the inventor of the ‘V’ for victory sign. He had been using it for years, albeit to signify Ancient Egypt. With his Brazilian cigars and bulldog jowls, he bore an uncanny resemblance to Churchill and could mimic the Prime Minister’s voice. Whether the Service ever employed this talent remains open to conjecture.

Ian Fleming, a lieutenant commander in Naval Intelligence, worked with B5b and would later model “M” on Maxwell Knight and Le Chiffre in the first James Bond story, Casino Royale, on Crowley. The Service was already feeding Rudolf Hess doctored horoscopes. Fleming suggested the Beast be smuggled into Germany and entrap the Deputy Führer with further esoteric bait. When Hess was captured, he proposed sending the Beast to Wormwood Scrubs in order to wean out information via a magical dialogue.

Sometimes Crowley’s activities verged on the bizarre. Another colleague, Lord Tredegar, worked for MI8, which monitored the flights of enemy carrier pigeons. Tredegar and his associates were keen falconers and their birds hunted pigeons suspected of spying. They launched a pigeon deception plan over the English Channel. The released birds were to invade Nazi pigeon lofts and bewilder the Abwehr. On the first drop, most of the birds were sucked into the plane’s slipstream and ‘defeathered’. On the second, the birds were put in paper bags and for a few days allied pigeons overran the Germans. Being ‘homers’, however, the pigeons decided to return. The plan frustrated, Tredegar complained to Lady Baden Powell and was promptly clamped up in the Tower. On his release, he hired Crowley to concoct a spell. Tredegar’s arresting officer fell painfully ill and almost died.

The Tredegar story is more one of magic than espionage, but it shows how the two mingle. In the Crowley Archive, which Gerald Yorke bequeathed to the Warburg Institute, there is a cordial invitation from Tredegar to his countryseat in South Wales, sent in 1944. There are letters from Tom Driberg referring cryptically to mysterious rendezvous and unnamed contacts. Crowley’s relationship with the Service spanned more than thirty years. Is there more waiting to be revealed?

Aleister Crowley, British Intelligence and the Occult

Secret Agent 666

Richard B. Spence (Feral House)

(Fortean Times)

Spence, a professor of history at the University of Idaho, makes a reasonable and well-researched case: there are no hypotheses on one page that spring into fact on the next and each chapter ends with an exhaustive attribution of sources. The link between magic and espionage is an ancient one. Nevertheless, to use such an extravagant self-publicist as Crowley as an agent seems improbable until one considers that it was the very unlikelihood of this that may have recommended him to a string of spy chiefs. After Admiral Hall, this included J.F.C.Carter, head of Special Branch, and the enigmatic Maxwell Knight, chief of B5b, a section of MI5 charged with countering foreign subversion. Likewise, it may seem extraordinary that such a supremely self-interested and unconventional being as the Beast could give a fig for King and Country yet his own description of his “Bill Sykes’ dog” brand of patriotism in The Confessions rings oddly true.

Crowley’s spying casts an interesting new light on his other activities. Spence plausibly presents scarlet women, male lovers, and friends as fellow operatives, including Tom Driberg and more surprisingly Gerald Yorke. It is extraordinary how many of Crowley’s secret service contacts were occult aficionados. Magical retirements in the States take place in areas of military importance; the commune at Cefalu is a convenient point from which to observe the manoeuvres of Mussolini’s navy. Anticipating CIA experiments with mind-altering substances, Crowley spikes people with mescaline, summarising the results in a (lost) work called The Cactus. Despite the best efforts of Spence and Naval Intelligence’s Ian Fleming, the jury stays out on Agent 666’s role in Rudolph Hess’s flight and detention. Nevertheless, the deputy Fuehrer’s protest to the Red Cross concerning hallucinations and food dosed with “Mexican brain poison” only bolsters conjecture.

Crowley’s Great War exploits are the focus of Spence’s book. After this, the picture becomes murkier. Crowley is involved with Nazi-influencing occult groups in Germany. He colludes with Walter Duranty, the American journalist who becomes a big shot in Stalin’s Russia. He spies on the turncoat Gerald Hamilton in Berlin. He mixes with a sinister coven in Cornwall then another group engaged in subversion and honey traps, which worries Philby during the Second World War. Paragraph after paragraph ends with a question, many setting worthy markers for future investigation of links to Rudolph Steiner, Nikola Tesla, Gurdjieff, and a host of crackpot organisations. Ultimately, however, the process grows frustrating, the parade of eccentrics bewildering. There is, as Spence acknowledges, “a sense of looking at the scattered pieces of some great jigsaw puzzle”.

In his introduction, the author anticipates this dilemma. Most of the secret service records pertaining to Crowley, particularly on the (unhelpful) British side, are missing, destroyed or unavailable: circumstantial evidence and informed speculation play a far larger role than he would prefer. Spence has made a brave attempt but it remains too soon to place “patriot” Crowley in the same pantheon as Lawrence of Arabia. In his espionage activities, as in much else, the Beast leaves us in the dark.

Aleister Crowley: The Beast in Britain

(FT review of Gary Lachman’s map)

Aleister Crowley’s extravagantly nomadic life is a gift for mapmaker and psychogeographer alike. Continuing in the tradition of Phil Baker’s outstanding City of the Beast, which investigates Crowley’s London haunts and is cited as a reference, Gary Lachman provides an attractively produced and packaged map of Crowley’s Britain. Featuring such beastly watering holes as the Café Royal and the Fitzroy Tavern, the London section reveals the Streatham address where Crowley discovered masturbation and the square in Mayfair where he celebrated his last erection. A separate timeline lists 1941 as the dread year of dysfunction. Surprisingly, this gives Crowley’s death as 2 December 1947 when all other sources record his passing as the first of the month.

Lachman, a founding member of Blondie, known for writings on the occult that include a book on Crowley, magick, and rock and roll, charts the Beast’s lairs, from his Leamington Spa birthplace to the cemetery in Brighton where he was cremated. Illuminated by an accompanying commentary, the map features Boleskine House that haunts the shores of Loch Ness, Beachy Head, a favourite climbing spot, and Netherwood, the bohemian Hastings Boarding House where Crowley spent his final years, now regrettably replaced by a close of new-build houses.

Other landmarks include Ashdown Forest where Crowley “is said to have performed rituals with Winston Churchill in order to fend off the Nazis”. This refers to the legendary Operation Mistletoe of 1940, with the Beast’s collaborator more usually identified as Ian Fleming wearing his Naval Intelligence hat, though as Lachman concedes, “Sadly, this remarkable act of patriotism remains uncorroborated”.

In writing of the Battle of Blythe Road, the Hammersmith temple of the Golden Dawn that a “masked and daggered” Crowley tried unsuccessfully to repossess in a magical duel with Yeats in 1900, Lachman writes: “Yeats – whom he considered a ‘quite unspeakable person’ – refused Crowley a desired initiation”. Who is “unspeakable’? Yeats? In fact, it was “weary Willie…that lank, dishevelled demonologist”, as Crowley called him, who described the Beast as “an unspeakable mad person”.

Nitpicking aside, there is a lot of appeal in this impressive project, making it a must-have for Crowley fiends. Now that Baker and Lachman have opened the geographical floodgates, a Crowley world atlas is clearly called for. This would chart his exuberant presence in Paris, Berlin, Mexico, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the United States; map his walks across China and Spain, the mountains he scaled in the Himalayas, and highlight such potential tourist shrines as the ruin that was formerly the Abbey of Thelema in Sicily and the Cairo apartment where Crowley received The Book of the Law.

“Aleister Crowley, National Treasure?” asks Lachman. Not yet, but maybe he’s getting there.

THE BEAST GOES ON: Aleister Crowley & Rock

A SEARCH ONLINE will turn up scores of songs called “Do What Thou Wilt”. Jay-Z even sported the words on a T-shirt. The phrase was coined by Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) known, much to his own amusement, as the Great Beast 666, the Wickedest Man in the World.

Born into a wealthy family of fanatical Christians, Crowley rejected their beliefs and spent his youth travelling the world, climbing mountains, canoodling with scores of male and female lovers, and experimenting with every drug under the sun. He was a writer, poet, painter, and arguably the greatest exponent of the occult of the twentieth century. He was also a spy, employed by British Intelligence agencies throughout his lifetime, a fact I have explored in two books.

“Do What Thou Wilt”, is not an invitation to do anything you like, but instead a call to discover who you truly are and what you should be doing and applying your will to that end. It certainly appealed to the American rapper Ab-Soul who used it for the title of his 2016 album. In a YouTube clip, the rapper cites Crowley’s influence on the Beatles and Led Zeppelin as the key to his own interest. But the Beast’s impact can be traced much further back than that.

Born in 1923, Harry E. Smith was a visual artist and filmmaker, who compiled the iconic Anthology of American Folk Music, drawing from his extensive collection of out-of-production 78 rpm recordings. Issued in 1952, these songs had a huge influence on the folk scene and artists such as Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. A beat and an eccentric, Smith was also a life-long occultist who was consecrated as a bishop in Crowley’s church, The Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica.

Another early disciple was Joe Meek, Britain’s answer to Phil Spector and composer of the revolutionary worldwide hit ‘Telstar’. Said to be Margaret Thatcher’s favourite record, it was made in the ramshackle home studio Meek built in his flat on the Holloway Road. A brilliant and innovative record producer, Meek’s judgement was occasionally flawed, a fact not unconnected with his huge intake of amphetamines and barbiturates. He told Brian Epstein not to take on the Beatles and asked The Raiders to get rid of their hoarse, rubbish singer, 16-year-old Rod Stewart. The Raiders then became the Moontrekkers, who recorded ‘Night of the Vampire’, complete with creaking coffin lids and an authentic Joe Meek scream, that was stopped at number 50 in its march up the hit parade by the BBC banning it due to its effect on people of a nervous disposition.

Highly neurotic and temperamental, Meek was brought up as a girl for the first four years his life – his mother had wanted one – and was gay at a time when the penalties were severe as he learnt to his cost when arrested for importuning in a public lavatory. His erratic behaviour was legendary. After groping Tom Jones, he trained a starter pistol on singer and band to make them play what he wanted. He held a shotgun to the temple of drummer Mitch Mitchell – later of the Jimi Hendrix Experience – to compel him to play a drum pattern correctly. Meek had a passion for spiritualism, Crowley, and the occult, planting microphones in graveyards, and was convinced he could communicate with a talking cat and aliens. He held seances to contact the spirit of Buddy Holly, whose death on 3 February 1959 he claimed to have foreseen. On the same date in 1967, after first shooting and killing his landlady, who had frequently complained about the noise, Meek reloaded his shotgun and trained it on himself.

A similar gory end awaited our next Crowley acolyte, the R & B multi-instrumentalist Graham Bond, who introduced the mellotron and Bach to popular music. Bond was adopted at birth and grew obsessed with Crowley in his teens. Finding the Beast had spawned an illegitimate son in his home county, Essex, Bond inevitably concluded Crowley was his dad. After Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce left the Graham Bond Organisation to join Eric Clapton in Cream, Bond increasingly devoted his music to magick, producing tracks such as ‘Love is the Law’. Drug ravaged, stricken by financial and relationship troubles, Bond threw himself under a tube train in Finsbury Park Station in 1971.

Bond had performed with Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, the school for so much Sixties’ rock. So had Jimmy Page, the best known of Crowley’s adherents, who also worked with Joe Meek as a session musician. Page opened an occult bookshop in Holland Street, Kensington called The Equinox and bought Crowley’s old home on the shores of Loch Ness, Boleskine House. The Led Zeppelin film, The Song Remains the Same, in which Page played a magician, was filmed there. Rumour connected the disasters that befell Led Zeppelin – the tragic death of Robert Plant’s young son and that of John Bonham, the drummer – with Page’s dabbling in the dark arts. Cowley’s influence is only subtly present in the music of Led Zeppelin, though Page did have “Do What Thou Wilt” inscribed on the vinyl of Led Zeppelin III. He dismissed claims demonic chants and invocations can be heard if you play the records backwards: it was enough of a challenge to play the music the right way round he pointed out.

Page made a very Crowley-influenced soundtrack for Kenneth Anger’s film Lucifer Rising. Anger was an American filmmaker and Crowley true believer, remembered principally for the lurid tales of celebrity scandal in his bestseller Hollywood Babylon. Anger hung out with the Rolling Stones during their ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ phase. Mick Jagger composed a soundtrack for another of his films. Page and the Stones also recorded a 1973 track together called ‘Scarlet’, the Scarlet Woman being a key concept in Crowley’s system.

Page and Anger had a dramatic falling out. The American director put a curse on the musician. Allegedly, Page did the same to our next Crowley obsessive, David Bowie. Bowie was another musician whose potential Joe Meek had failed to register. He and Page recorded together in 1965 and became friends. Page gave Bowie the martial riff for his 1970 song ‘The Supermen’. Things turned sour when Page visited the New York Townhouse where Bowie was staying in 1975, the peak phase, allegedly, of mutual cocaine use. Bowie was skeletally thin, living on milk and red peppers and obsessed by magick and occult Nazism. He believed Page was playing supernatural mind games and asked him to leave by the door or the window, the latter either in anger or in tribute to Page’s powers as a magician as they were on an upper floor. Terrified that Page had cursed him and might have gained possession of a fingernail, some urine or a strand of hair to ritually use against him, the story has Bowie immediately fleeing to the West Coast.

Page, allegedly, also put a curse on Eddie and the Hot Rods after they used a picture of Crowley wearing a comical pair of Mickey Mouse Ears to advertise their 1977 single “Do Anything you Wanna Do”, which demonstrated Crowley’s impact on punk was as profound as it had been on hippiedom. The band were almost immediately dropped by their label and various other disasters are claimed to have befallen them.

Bowie’s connection with Crowley was nuanced as the 1971 track “Quicksand” demonstrates. “I’m drawn unto the Golden Dawn, immersed in Crowley’s uniform of imagery” Bowie sings, the Order of the Golden Dawn being a late nineteenth-century magical organisation in which the poet Yeats waged magical warfare with the Beast. Though fond of emulating Crowley by dressing up in ancient Egyptian costume – Billy Eilish sported a photo of him so attired on her T-shirt at 2022’s Glastonbury – Bowie feels he is pulled between the light and dark, hardly surprising when you consider the fates of Joe Meek and Graham Bond.

Bowie took things even further on 1976’s Station to Station, a tour de force of an album he claimed he had no memory of making, where he references the Cabbala and White Stains, a book of pornographic poetry Crowley penned. Over time Bowie’s enthusiasm cooled. He would regret falling into the trap of “black magic, cabbalism and the Crowleyism of the times” – the mid-1970s – and dismissed, “That whole dark and rather fearsome never-world of the wrong side of the brain”. This does not tell the whole story. Some maintain the lyrics of his worldwide hit ‘Let’s Dance’ derive from a Crowley poem. The connection is tenuous. Less so is Crowley’s influence on Bowie’s remarkable farewell. The video for ‘Blackstar’, itself directed by a Crowley enthusiast, is packed with magical imagery. Lines such as ‘a solitary candle at the centre of it all’ echo Crowley’s Sapphire Ritual. In the video for his leave-taking song “Lazarus”, Bowie poignantly exits into a wardrobe dressed in the same bodysuit he wore for astral travel in Los Angeles in the 1970s.

A byword for Satanism, though arguably not a Satanist, Crowley has predictably had a huge impact on Metal. Iron Maiden’s ‘Moonchild’ is inspired by the Beast. Their lead vocalist, Bruce Dickinson, brought out a film called Chemical Wedding in 2008 in which Crowley reincarnates in the body of a Cambridge professor played by Simon Callow. Ozzy Osbourne described the Beast as a “phenomenon”. Enthused by Crowley-designed tarot cards in the studio – the pack of Thoth – he and a couple of bandmates wrote ‘Mr Crowley’. The song views the Beast as a tragic figure and ingeniously rhymes ‘pure’ with ‘rapport’, the former a nod to Crowley’s gnostic belief he could immerse himself in depravity and emerge smelling of roses.

Further afield, Raul Seixas (1945-1989), known as the ‘Father of Brazilian rock’ was introduced to Crowley in the 1970s by Paulo Coelho, who would achieve worldwide fame as the author of The Alchemist. Together they wrote a huge hit which translates as ‘Long Live the Alternative Society’, which references Crowley. They planned to create an anarchist free state based on ‘Do what thou wilt’ in the province of Minas Gerais. Instead, they were arrested and imprisoned by the ruling military junta. Seixas would recite Crowley’s declaration of rights, Liber Oz, at concerts. Every year on his birthday, thousands parade through the streets of downtown Sao Paulo to commemorate the man they call ‘Maluco Beleza’, which loosely translates as ‘Groovy Nutcase’. Seixas’s YouTube homage to Crowley, ‘Loteria de Babilonia’, is interspersed with animated images of the Beast.

Crowley’s modern-day followers are particularly concentrated in America, where Daryl Hall and Lady Gaga have been receptive to his teachings. In 1991, Red Hot Chili Peppers brought out their breakthrough album ‘Blood Sugar Sex Magik’. Their guitarist, John Frusciante, has also included the Beast’s texts on solo albums. Sex magick is the belief that by focusing your will on a specific objective during lovemaking you can bring about the required result. It is a key ingredient of Crowley’s system. Nearer home, Damon Albarn made use of a recording of Crowley’s voice in his 2014 opera Dr Dee. Dee was the court magician of Elizabeth the First as well as one of her principal spies. He believed he had mastered Enochian, the language of the angels, and Crowley can be heard reciting this on the track ‘Edward Kelley’.

Crowley believed a new age of childlike rebellion would really kick in around 1965. Coincidentally or not, 1965 is viewed as Year Zero for the great musical leap forward of the psychedelic era. The Beatles put Crowley on the cover of Sergeant Pepper. John Lennon said that “do what thou wilst” (sic), was what the band were about. According to Richard Kaczynski, citing an interview in Rolling Stone, Paul McCartney claimed that magic held the Beatles together, adding he meant magic with a k, which is how it is spelt in Crowley’s system to avoid confusion with more common-or-garden conjuring.

It is not hard to understand Crowley’s appeal for musicians. Fifty years before the word ‘hippy’ was invented he was a free-loving, drug-taking, commune-living, east-meets-west yogi spreading a gospel of personal liberation. That doctrine, usually compounded by heavy drug use, had a disastrous effect on Joe Meek and Graham Bond. But does that invalidate the music that Crowley or his school of thought inspired?

Click below to hear Richard talking on Chocolate Radio about his life, writing, and the influence of Aleister Crowley on musicians, with tracks by Joe Meek, Graham Bond, Jimmy Page, David Bowie, Ozzy Osbourne, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Ab-Soul.

Made at the tip of Africa. ©