The Names of the Hare

An appreciation of Barry Flanagan

(Photo of Barry finding dead hare courtesy of Mark Jones who owns the copyright)

In 1983, Barry Flanagan and Seamus Heaney collaborated on an illustrated version of The Names of the Hare, the Irish poet’s rendition of the medieval poem. Beneath three characteristically graceful leaping hares, there is a roll call of the impish creature’s names, this being the only way the hunter could get the better of it. Sometimes during a conversation Barry would pause, strain forward and sniff the air, with his finely etched features and clumps of stubble the razor had missed, resembling the animal he had made his trademark. The identification went further: many of his hare-themed sculptures, prints and drawings have strong autobiographical overtones. The animal’s protean nature chimed with his.

Barry’s first hare was cast in November 1979. Up to then, the sculptor had occupied a worthy but straitened position amongst the avant-garde. He had grown to dislike the way “money punishes art” and had even resorted to making lino-printed “funds”, Flanagan money that could be redeemed against his estate upon his death, which he exchanged for jobs and materials. He had a wife, two young daughters to raise, and a CV made up of casual labouring jobs and shows that had caused hardly a stir. Riding a white bicycle around a gallery while obliging visitors cut Yoko Ono’s clothes off with scissors did not help with the rent. Glimpsing a hare on the Sussex Downs, buying a dead one from the butcher and bringing it to the foundry to model, allowed Barry to leap away from pure conceptual art and embrace the “concept of trade”. He attended business courses and took to wearing a tradesman’s cloth cap and a bespoke suit with sketchbook pockets, a type of costume he would persist with when living on Ibiza, whatever the temperature. “When out of the garret one no longer works alone but finds a place in the scheme of things,” he remarked.

Mercurial, mythological, magical, the hare was an immediate success and Texan billionaires, French wine producers and Japanese hoteliers jostled to buy one. Barry was photographed by Snowdon for Vogue Magazine and represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1982. He had arrived yet was still driven by the prankster spirit that had inspired him to place a turd-shaped stone to the rear of Henry Moore’s Sheep Piece at the Silver Jubilee Exhibition in Battersea Park. The hare, after all, was ‘the wild one, the skipper, the hug-the-ground, the lurker, the race-the-wind, the skiver’. Moreover, it had pedigree in the same out-there territory as Barry’s initial explorations, consider Joseph Beuys’s 1965 performance art piece How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, in which the German artist spent three hours cradling the dead animal in his arms as he whispered the meaning of his drawings to it, with honey and gold dust dripping from his head. It is probably not a coincidence (of which Barry was an adherent of the “no such thing” school) that the two artists – mavericks and shamans both – occupied adjoining rooms in the early days of Tate Modern.

Poetry not sculpture was Barry’s first love. He would describe himself as ‘the poet of the building site’ while a labourer. From the basement of Better Books in the Charing Cross Road, where the owner Bob Cobbing had installed a typewriter, Barry produced a weekly magazine called Silãns. This was 1964 and Barry was studying at St Martin’s School of Art where some of the fifty cyclostyled copies were given away every Monday morning. The rest were placed in the bookshop. He was drawn to concrete verse, attending the famous poetry festival at the Albert Hall featuring Allen Ginsberg in 1965 and delivered a silent lip poem in the Second International Exhibition of Experimental Poetry in the same year. He was delighted when he found a way to rhyme ‘cider’ with ‘crazy’, a feat very much inspired by the former. Concrete poetry served as well to provide titles for his fledgling sculptural work. The group of felt-stuffed pieces confined within a circle, which have the absurd, brooding appearance of characters from a play by Barry’s hero, the French writer and founder of Pataphysics, Alfred Jarry, is titled aaing i gni aa, first exhibited in Better Books and subsequently bought by the Tate. Another title, ‘Four Casb 2 ‘67’, seems to be drawn from the same enigmatic territory but is a matter-of-fact description of the materials employed and date of use: four canvas sandbags, number two, 1967.

I first met the sculptor on Ibiza in 1987. He had just moved to what he would describe as “this haunted, blessed place”. In his dusty green cord jacket and worn baggy denims, I took him to be another scruffy irregular of the artists’ brigade that caroused and occasionally put paint to canvas or pen to paper, drawn to the island by its climate, tolerant locals and cheapness. It took me a while to realize Barry had an international reputation and significant wealth. While living on the island, apart from properties in London and a room reserved at the Chelsea Hotel in New York, he would rent flats or buy houses in any place his career happened to collide with, such as Barcelona, Amsterdam or Dublin. He also acquired or rented several properties on Ibiza, even selling and then buying back his main house on the island. The beneficiary of the last shared the same first name as me and several people congratulated me on the windfall. Coming from a theatrical family, Barry was nomadic by nature, but instead of pitching a tent, he would acquire property wherever he happened to be. This was necessary for him he said and tallied with his sense of place.

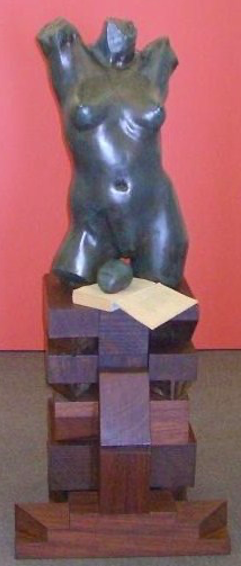

I would frequently visit him in his rambling house. Wearing loose-fitting Japanese robes or a wide-sleeved dressing gown, he would mull over titles for the pyramid-shaped works in mild steel, which looked to my untutored eye like hulks rusting amidst the overgrown weeds of the garden, or ask me to help him arrange a set of architect’s blocks, a nearly featureless black head, and a torso modelled on his wife Renate that had originally been a shop-window mannequin. He never seemed to find the right arrangement for the group. Most of the time, however, he seemed not to do much at all. It was beyond me how he had become so successful. I wondered if the island was turning him into a lotus eater. An old friend of his in London, however, told me this was always how Barry operated. Not for him a 9-to-5. He could lie fallow for considerable periods but was very productive when he toiled. Drinking a lot, mainly whisky, he made it plain he was a “pissed artist” not a “piss artist”.

A conversation with Barry was often a daunting, multi-dimensional mind-game. “When I lob a ball, I expect a decent return …” he would say. His analogies were frequently drawn from tennis or cricket. Certain key terms pervaded his speech: “civility”, “address” (the verb), “as a student”, “practice”, “trade”, and he could be just as sculptural with language as he was with bronze. “Don’t pay homage to a dead weight!” he once admonished me, in what I took to be a reference to an exacting muse. It was useless to engage him in small talk. An enquiry as to his health or a comment about the weather would be met by anecdotes concerning the experimental art scene of the 1960s. Whether you were familiar or not with the people he mentioned did not seem to matter. He delighted in wordplays. There is a drawing he made in the 1970s called Keeping ones own tracts open, which consists of that phrase towards the bottom of the sheet with the same words written backwards beneath it. The sheet is empty. Barry was very much keeping his tracks open. The joke is ‘tracts’, the most prescribed of literary forms.

He used the walls of his Ibizan house as a notebook, on which he scribbled haikus and aphorisms in pencil or red-brown ink. Some were droll: is it my fault I chose life over employment? A rejoinder he had made to a belligerent tax inspector. Others illustrated his guiding principles: true judgment resides in the heart. Others, still, such as the hues of the ripple, crystallized his multi-faceted approach. Once he asked me to arrange for a photographer to take shots of some birds he had drawn on the wall. This subsequently became an etching.

One day he gave me a shoebox with five clay pots in it and told me to take it to the museum. There were two to choose from, archaeology or contemporary art. His pinch pots, as they were called, had an unfinished prehistoric look so I spent half an hour of mutual bewilderment with the director of the former. More fruitful was a connection I established a short while later with the art museum, which led to Barry being offered a show in the sixteenth-century building’s cellar, which had originally housed the gunpowder and animal feed of the city garrison. The first meeting was at his house, an exceptionally warm spring day. The sculptor made a blazing fire and with great courtliness drew the sofa the museum director was sitting on as close as possible up to it. The elements mattered not a jot when it came to hospitality.

Compared to Barry’s usual stamping grounds Ibiza was a very provincial gig, but he took to the challenge with gusto, filling the space with exquisite drawings, hangings, and mild steel pieces, which he had the brilliant idea of ringing with salt from the pans at Salinas. He recreated a work called Light on Light on Sacks, first shown at the Hayward Gallery in 1969. This consisted of a heap of thirty hemp and flaxen sacks stuffed with carob beans acquired, on a sale or return basis, from a puzzled farmer in San Carlos. A projector shone a square of light onto them. After the exhibition had been extended by popular demand, they attracted rats that ripped open the sacks and feasted on their contents. Barry went AWOL a couple of times the week of the hang and it seemed touch and go whether he would be there for the opening. The day arrived and a morning of fruitless searching ended when we found him asleep on a couch in the basement gallery surrounded by his treasures.

During the hang, he finally worked out the proper arrangement for the architect’s blocks and placed the now gilded torso on them with the round black head gazing up at the belly. Beneath the round black head Barry put a photocopy of a poem I had come across in The Penguin Book of Spanish Verse called Head of the Goddess in my Hands, which treated of the way sculpture endures beyond the life of its creator, I had been struck by the fact that the date beneath the title, 654 BC, was that of the foundation of the city of Ibiza by the Phoenicians and discovered the goddess of the title was the island’s presiding deity, Tanit. The poem’s author Antonio Colinas lived on the island and came to the museum. He was happy for the poem to be used but said a photocopy would destroy the exhibition, so we substituted the book, opened at the relevant page, instead.

Fortunately for Colinas, Barry did not use literature in sculpture in quite the same way he had with John Latham in the Sixties. Latham was a part-time tutor at St Martin’s, which at that time had a tradition of inviting radical visiting lecturers, such as Alexander Trocchi and R D Laing. Another was the American Clement Greenberg author of Art and Culture, which argued that the best avant-garde art was American and dismissed British Art as ‘too tasteful’. Bridling at this and the polemical tone of the book in general, Latham, Barry and a group of St Martin’s students organized an event called ‘Chew and Still’, in which they chewed a third of the book’s pages. The result was spat into a small glass flask, where it was submerged in sulphuric acid until the solution turned to sugar. Yeast was added, the mixture left to ferment, and then poured into a glass vial Latham labelled ‘the essence of Greenberg’. Unfortunately, Latham had borrowed the book from the college library and was sacked for his efforts. The Museum of Modern Art in New York later acquired the piece, now called Art and Culture. Barry donated Head of the Goddess in My Hands to the Ibiza Museum of Contemporary Art, and it is on permanent display, among the most romantic and lyrical of his works.

In September 1992, we took the show to Palma and while there hired a car to visit the celebrated Spanish artist, Miquel Barceló. Barceló spent four months of the year at his home in the north of the island, dividing the rest between Paris and Mali. Barry was driving, and I asked him why he was keeping his eyes so determinedly fixed on the road and ignoring the terrain. He explained he disliked being dwarfed by mountains. We hit on the term “invertigo” to describe this. Later this chimed with something his mother Monica told me. By being born in 1941, Barry had spent the first few years of his life effectively as an only child, his two older brothers and sister evacuees in North America. Their return at the war’s end and the attendant decline in attention came as a terrible shock. In some senses, the sculptor’s art was a battle to be heard. Nothing riled him more than to be ignored or made to feel underestimated. As we continued our journey up the rugged west coast, Barry remarked there was so much stone a sculptor could get indigestion.

In 1994 I upped sticks from Ibiza and returned to England. I was like the fabled Spanish general who had not a clue where he was going but wherever it was, he would lose his way. Barry chided himself sometimes for neglecting old friends, but this was never my experience. He knew I needed to connect with my surroundings so underwrote a tour of quarries. I did this in the company of an old friend, the actor Oengus Macnamara. We visited Doulting, the source of the stone for Wells Cathedral, and Ham Hill with its Saxon forts. Gradually, it dawned on me that there was a subtext. Cracking the code of Barry’s telephoned instructions led us to Beer in Devon in pursuit of Fred Newton, in youth an apprentice banker mason at the local quarry, who had given Barry a job in 1959. We were directed to Banbury, where Barry had undergone a brief apprenticeship as a dental technician with the exquisitely named Mister Mold, and to Oxford, where in 1975 he had blocked out one of Michael Black’s Philosophers for the Sheldonian Theatre while working as a stonemason. My travels resulted in a report on stone and quarries called No Stone Unturned, which I presented to him in the Groucho Club. Afterwards, I committed the unpardonable sin of sitting on Ian Board’s chair at the Colony Club, which I compounded by falling off it.

What baffled me most in England was why I had abandoned my life of pleasant hedonism on Ibiza and come back. A sort of answer was provided when I met a profoundly deaf fourteen-year-old girl at a reunion of old friends who turned out to be my daughter. She had a flair for art. A couple of years later it became necessary to fund her studies. I appealed to Barry. In response, I received a letter consisting of one phrase: Long a moving line. On one level, the words seemed to refer to the emotion produced by my letter. But another interpretation was the line was my family which, with this discovery of a daughter, was in moving on. Barry told the college he wished to fund another student should my daughter not complete her studies. There is an abundance of such stories. One thing that distinguishes the hare from the rabbit is its heart, which weighs up to 1.8% of total body weight compared to the latter’s 0.3%. ‘Great-hearted, life enricher, selfless giver,’ words that fit Barry like a glove.

For more see my book, With Barry Flanagan – Travels through Spain and Time (The Lilliput Press)