Richard C McNeff

Author

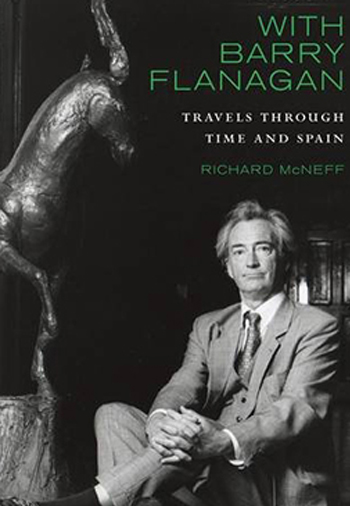

With Barry Flanagan Travels through Time and Spain (Lilliput Press)

A vivid account of a close friendship that evolved into a working relationship when Richard McNeff became ‘spontaneous fixer’ (Flanagan’s description) of the sculptor’s show held in June 1992 at the Museum of Contemporary Art on Ibiza, where they were both living. McNeff was to gain a privileged insight into the sculptor’s singular personality and eccentric working methods, learning to decipher his memorably surreal turns of phrase and to parry his fascinating, if at times unsettling, pranksteresque quirks.

In September 1992 Flanagan and McNeff took the show to Majorca, resulting a lively visit to the celebrated Spanish artist Miquel Barceló. The following year McNeff was involved in Flanagan’s print-making venture in Barcelona and in his Madrid retrospective. Flanagan rescued him from a rough landing in England in 1994 by commissioning a tour of stone quarries there. Subsequently McNeff ran into a fourteen-year-old profoundly deaf girl who turned out to be his unknown daughter. She had a talent for art and the generous sculptor was instrumental in helping with her studies.

Late in 2008 Barry was diagnosed with motor neurone disease. By June 2009 he was wheelchair-bound. Two months later he died, and McNeff read the lesson at his funeral. Fleshed out with biographical detail, much of it supplied by the sculptor himself, supplemented by photographs and details of the work, this touching memoir is the first retrospective of a major Welsh-born artist. With Barry Flanagan captures the spirit of this remarkable Merlinesque figure in a moving portrait that reveals a true original.

ISBN: 978 1 84351 322 3 – hardback (also in Kindle) – Lilliput Press

REVIEWS

“It is a very personal and often hilarious recollection of McNeff’s support of Flanagan … a compelling portrait of this great artist.”

Barbara Dawson: Irish Arts Review

“Your book is so rich in Barry-lore and response to his work that it more or less makes other biographies unnecessary.”

Catherine Lampert (former director of the Whitechapel Gallery)

“This book is chock full of ‘Flanagan anecdotes’ and as a reader I felt like I was being let in on a secret of these bohemian artists who had lived in Ibiza and their hippy and boozy lives. It is a fascinating account and whether you are familiar with Flanagan’s artistic work or not, this is an extremely interesting biography which is a great read that will leave you more knowledgeable about the artist as well as entertained by the stories.”

The Dublin Duchess

“A cracking memoir – funny, informative, elegiac and thought-provoking. Barry Flanagan cast leaping leporines, spent his final years on Ibiza and was born in Prestatyn (where I attended a wonderfully 1930s prep school), but these bare factoids are also connected with the fundamental laws of the Universe. He was actually a magician with words and ideas, and his playful probing into public minds and private lives was worthy of Gandalf himself. Ibizaholics will delight in McNeff’s expert skewering of island life and mores, while the artist’s hilarious two-step with museum directors and local hacks is sheer joy. The journey into Flanagan’s Jarryesque modus operandi is art writing at its best, self-deprecating prose that makes every page a delight. Lilliput Press have risen magnificently to the occasion with pruned-back design, a sensible typeface, nice, creamy paper plus a sprinkling of helpful illustrations. In short, like a glittering vernissage you cannot afford to miss.”

Martin Davies (founder of Barbary Press, Ibiza)

Miquel Barcelo and Barry Flanagan, Cerámiques i Dibuxos (ceramics and drawings)

Enrique Juncosa and Richard McNeff.

Published to coincide with the exhibition of the artists’ work at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Ibiza 27 of April to 31 October

2012. Contains my account of the artists’ first meeting in English, Spanish and Catalan.

Piece in the Guardian to coincide with Barry’s show at Tate Britain (27 September-2 january). There is also a picture gallery of his work.

‘Hare today, but not gone tomorrow’

(www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/sep/26/barry-flanagan-tate-britain-exhibition)

BARRY FLANAGAN - SCULPTOR

BARRY FLANAGAN: IN APPRECIATION

When I first saw Barry, at a wedding in Es Figueral in the late eighties, going by his dusty denim suit and general boho air, I judged him to be another of the many artists on Ibiza who eked out a modest, at times precarious living in pursuit of their calling. It was not until sometime later that I discovered he was an artist-star as celebrated in Tokyo as he was in London, Paris and New York.

Barry was born in Prestatyn, Wales, in January 1941. In his youth he tried his hand at labouring, the cello, quarry work, dental work, and making props on the film set of Cleopatra. All of these disparate callings appeared, in one way or another, in the work that began to emerge from his time at St Martin’s School of Art.

In the Sixties he was firmly associated with the avant-garde and worked in performance art, drawing, film and found art. His reverence for materials and form was immediately noticeable and he was equally at home with clay, cloth, rope, sand and stone. His work was also distinguished by evocative, playful titles such as Sixties Dish, a cello reflected by a mirror on a sofa. He narrowly avoided becoming the target of the kind of ridicule that was heaped on his friend the American minimalist Carl Andre, when the Tate bought the latter’s bricks, for works such as Barry’s own Pile, literally just that – a pile of differently coloured blankets. What marked the sculptor out as well was his humour and subversiveness, inspired to a considerable degree by the French writer Alfred Jarry, inventor of Pataphysics, the “science of imaginary solutions”. These qualities were implicit in the bronze hares he started modelling in the late seventies, which brought him rapidly into the public eye.

I once told him a talent such as his would inevitably find recognition and was surprised at how angry he became. Resentful of the way “money punishes art” and realising the Flanagan money he was producing, notes drawn and signed by him for £5, £10 and £20 pounds, had a limited spending power, Barry foreswore the clichéd pose of the artist starving in a garret, and took some business courses, anticipating Brit Art in his lack of squeamishness concerning success and wealth as well as in the remote method of production he favoured for the bronzes.

What began as a friendship between us took on a more workmanlike direction and I became his “spontaneous fixer” for a period in the early Nineties. Among other things, I assisted him on the show he shared with the French sculptor Marcel Floris at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Ibiza in 1992, which we later took to Palma. This in many ways was the equivalent of the Rolling Stones gigging in a local pub, but he set to with gusto and the results were fascinating. The word genius is bandied about with great freedom these days, but seeing him in action was a revelation, and being present when he was literally struck by an idea, a lasting privilege.

Barry passed away on August 31 after becoming afflicted with motor neurone disease. He has, in the words of Auden on Yeats, “become his admirers”. The obituaries speak of “Britain’s best-known and most controversial modernist” (The Daily Telegraph) and of “one of the most versatile, imaginative and radical sculptors of his generation” (The Independent). He will be remembered in other ways as well, such as by the “Warm amen” to The Independent obituary posted on the internet by Tony Crofts of Bristol, in which he recalls the sculptor’s personal generosity in a moving anecdote.

How many must have seconded that amen amongst the congregation who filled the church of Puig de Missa in Santa Eulalia for the service held on the morning of the eleventh of September. The fact that the key had taken an hour to turn up and it seemed at one point that proceedings might have to take place outside was neither surprising nor unappealing to those who knew Barry.

Eventually the doors were opened, and Jessica Sturgess, Barry’s partner, recited “Head of the Goddess in my Hands”, a poem by Antonio Colinas, which open on the page of The Penguin Book of Spanish Verse forms part of the work of the same name that can be found on permanent display at the Ibiza art museum. The date beneath the title, 654 BC, is the date of the foundation of the city of Ibiza; the goddess is Tanit, and the poem speaks of how the work of a sculptor endures beyond him.

Flan, one of Barry’s daughters by his first marriage to Sue, the other being Tara, recited, with feet bare, Jarry’s extraordinary description of God – “the tangential point between zero and infinity”. Later, in his sermon, the priest referred to this with some puzzlement, a detail Barry would have loved. The sculptor’s startlingly original collaboration with Hugh Cornwall of The Stranglers was also played: “Mantra of the Awoken Powers”, in which Barry, recorded down an answer phone, recites the poem by Sex W. Johnson against a background of electric guitars. More conventionally, there was a Eulogy by Enrique Juncosa, director of the Irish Museum of Modern Art, where a retrospective of Barry’s work was held in 2006, hymns and a reading from Ecclesiastes.

In the afternoon, family members, friends and fellow artists, including some of the leading figures in the world of European arts, gathered at the family house, Barry’s former studio on the road to San Carlos. Sandwiched between performances by two groups, various friends related anecdotes or recited pieces in tribute to Barry, ending most movingly with farewells from his children by Renata Widmann, Alfred and Annabelle.

To those who will miss seeing the sculptor on the island, complete with heavy corduroy jacket in the height of summer, pausing with a slightly distracted air to admire the ironwork on a grille or engage workmen in conversation, there are relics of his to be found. Apart from “Head of the Goddess”, there is the delicate Kourus horse he gave to Santa Eulalia and a wonderful ceramic that can be seen in the garden of a restaurant on the town’s promenade. More even than these, however, is the gratitude he left in the hearts of the many he helped and inspired with unstinting generosity. Barry was someone who enhanced both his surroundings and those around him, not just with works of endlessly-suggestive wit and beauty, but also by deeds dictated by the heart.

Originally published in IbizaNOW

head of the goddess in my hands

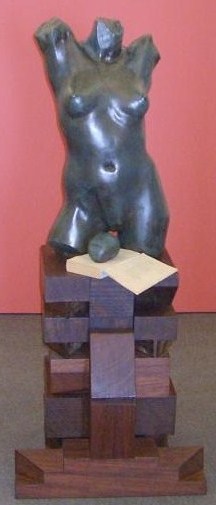

On a line with the prancing hare, placed between it and the hanging cloths executed in the seventies, is the remarkable golden torso of a woman and the almost featureless black head that gazes up at her, both mounted on rectangular wooden architect’s blocks. The head rests on a large paperback edition of The Penguin Book of Spanish Verse , opened at a poem entitled Head of the Goddess in my Hands, which bears beneath these words the date 654 B.C., the year of foundation of the city of Ibiza. The head in the poem is that of the Punic goddess Tanit, but the poem essentially treats of how the work of a sculptor endures beyond him:

Made at the tip of Africa. ©