THE SOUND OF 65

THURSDAY, 8 APRIL 1965: The Graham Bond ORGANisation’s fractious gig at Klooks Kleek, West Hampstead, and a subsequent encounter with two acid-spiked Beatles in Soho.

EVERYBODY’S HAIR WAS GETTING LONGER. Ginger Baker’s was a red fuzz framing his sucked in cheeks, pinned eyes and nicotine-veneered teeth. It was a face that threatened to eat you and your kids for breakfast. They’d just listened to ‘Play with Fire’, the B-side of the Rolling Stones’ current number one, ‘The Last Time’, and Baker was having none of it.

‘The tossers couldn’t play black blues to save their lives. Now they’ve gone all psycho wiv fairy ‘arpsichords an all.’

‘Psy-che-delic,’ corrected Alexis Korner, in his gravelly, well-spoken voice. He appeared to be black with his afro hair, cool shades, and full lips. In fact, he was a Paris-born melange of Austrian Jew, Greek and Turk.

‘Psy-fuckin’-cho! I’m amazed Charlie don’t roll over and die of shame.’

Before migrating to the Stones, Charlie Watts had been Baker’s replacement in Korner’s Blues Incorporated. Korner smiled indulgently and passed the joint. The sweet pungency of red Lebanese enveloped the living room of his fusty flat. A television, with the volume turned down, was showing ‘Juke Box Jury’ in direct line of sight of Jack Bruce, lounging on the sofa.

‘I thought the harpsichord was pretty cool,’ said the Scotsman in his lilting burr.

‘That’s because you’re a fuckin’ cellist who moonlights playin’ R & B!’

Bruce gazed with stoned serenity at his bandmate, too inured to Baker’s effortless vitriol to react.

There was a ring at the front door. “Nico”, Korner’s eldest son, peered through the peephole and turned the latch. The newcomer tottered into the room in Cuban-heeled Chelsea boots, a black cloak, and striped hipsters that were too tight for his pudgy frame. He had black penetrating eyes, a bloated face, and a Fu Manchu moustache. He knew everyone except Will.

‘Meet the soundman,’ growled Korner. ‘Will, this is Graham Bond.’

‘I ‘ope ‘e’s a sound man,’ Baker spat out, glaring at his neighbour.

‘He’s not a sound, man, he’s a man, man.’

Bruce was out of his gourd. The others were just out of their heads.

‘Do what thou wilt!’ said Bond in Estuary English.

Will recoiled, too shocked to do anything other than reply: ‘Love is the Law.’

It was Bond’s turn to look startled. They faced each other like boxers about to exchange blows.

‘You dig Crowley?’ said Bond.

‘Dig him? I knew him.’

‘You knew my dad?’

Bond had landed the knock-out punch.

The musician was a Barnardo boy, born an orphan in Essex in 1937, the same year the Beast had sired an illegitimate son in the county. This made it obvious that Crowley was his dad. Will explained he had been the handyman at Netherwood, the bohemian Hastings boarding house where Crowley had settled in 1945 and died in 1947.

‘Gram, we need to ‘ave a catch-up,’ said Baker, rising and hustling Bond out to the bathroom.

Nico came in and demanded a quid from his dad.

‘Think I’m made of bread, man? What’s it for?’

It was six thirty. The gritty police drama ‘Z Cars’ was playing on the flickering black-and-white screen. Nico was due to hook up with ‘H’ and ‘Trippie Nickie’ in the ticket hall at Notting Hill Gate tube station. They would pool info about happenings in shabby flats in the Gate and Grove, before making off for one. Nico gave a petulant shake of his floppy hair. Korner pulled a red note from the pocket of his corduroy shirt, tossed the ten shillings at his son, and took a glug of Bulgarian plonk.

Bond and Baker re-emerged with glistening eyes and sprightly movements. They would remain fired up for all of ten minutes. Bond grabbed a Muddy Waters’ album from the stack next to the record player, placed it on his lap and commenced crumbling crystal-speckled black Nepalese Temple Ball into golden Three Castles tobacco.

‘Can’t you feel it happening, man?’ he said. ‘Year Zero! Everything’s in flux. Full speed ahead to the New Aeon. He knew, didn’t he? The Crowned and Conquering Child! The Beast dug it long before anybody else!’

‘Crowley was a creep,’ muttered Baker.

‘Yeah, if you believe John Symonds’ The Great Beast. He sensationalised and belittled the Holy Guru. He spat and trampled on Sacred Magick. Just wait till karma catches up with him. Have you tried LSD, man?’

Courtesy of a professor of physics at Imperial College, Will had. He agreed it was remarkable.

‘Give us a toke, Alexis!’ demanded Baker.

Korner took three rapid puffs, held the smoke down, then broke into a racking cough. He proffered the joint as though offering a peace pipe, which in a sense it was. Eighteen months before, Baker, Bond and Bruce had abandoned Blues Incorporated to form The Graham Bond Organisation. Korner had been a bit miffed, but his band was a revolving door, the launchpad, arguably, of the Rolling Stones, Free and Led Zeppelin. Korner was inured to the phenomenal success enjoyed by musicians who had thrived under his tutelage in the blues, long considered a backwater. It was a feat of humility that Graham Bond would prove far less agile at making.

Bond and Baker were starting to nod off. Both were registered addicts and received pure high-grade British pharmaceutical heroin on prescription, for which they queued at midnight outside the Boots all-night chemist in Piccadilly Circus. Baker’s addiction stemmed from the late 1950s when he had convinced himself that heroin, a staple of the scene, fuelled his virtuoso jazz drumming. Bond had only recently tipped over into the abyss, following a divorce and a sequence of personal crises that would continue to dog him. Ironically, Korner’s jeopardy was much greater. Allowing premises to be used for smoking cannabis had just been criminalised, and the penalties were draconian.

‘Smack!’ he muttered with distaste, gazing at the sleeping beauties.

‘You’re a pillock who hedges himself with talent just so ‘e can look cool,’ murmured Baker, without lifting an eyelid.

Three hours later, Will’s practised fingers were twiddling the knobs and levering the slides on the mixing desk, while he checked that the tape reels on the four-track were revolving smoothly. A crowd of heaving souls were crammed into Klooks Kleek, a gritty music venue on the first floor of the Railway Hotel, West Hampstead. It had been a storming set of jazz-infused rhythm and blues and had all the makings of an excellent live album. A pioneer in his use of the Mellotron, Bond was creating a hybrid of Bach and the blues on ‘Wade in the Water’. A berserk Baker thrashed at the drums. Bruce hammered the bass, producing a wild proliferation of notes. “You’re too fuckin’ busy!” Baker yelled. Will wondered if the tape had picked up the drummer’s exclamation.

The next number, the Baker-penned ‘Camels and Elephants’, featured a lengthy drum solo. Bruce joined in about halfway through, keeping time with Baker’s trademark double-bass drums. At first, the Scotsman hung back, but soon his booming notes began to take over. Highly sensitive to volume – if to little else – Baker raised his drumsticks above his head and hurled them at the bassist. “It will be a knife next time,” he shrieked as he vaulted from his stool and laid into his bandmate. With his trademark goatee jutting out, Dick Heckstall-Smith, the saxophonist, helped Bond separate the feuding bandmates. The crowd booed and catcalled. There was little damage, other than Baker pushing Heckstall-Smith’s cap off his head. No live record, however, would see the light of day. There was a sour mood in the van on the way back to Shepherd’s Bush, where the gear was stored. Reluctant to end the night on such a downer, Will hailed a black cab and went to Soho.

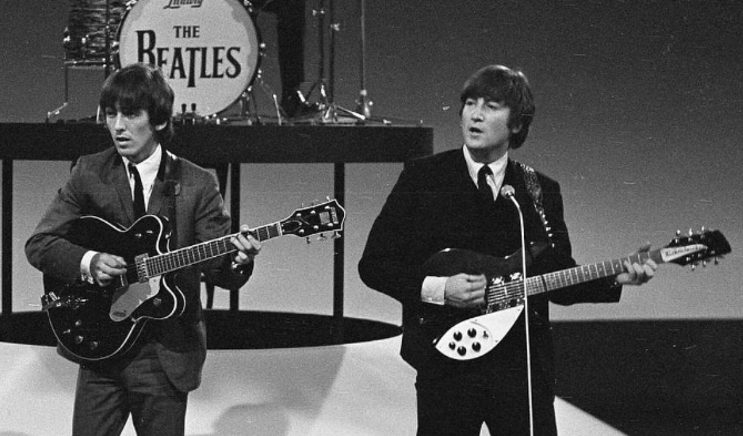

A tiny lift in the foyer of 7 Leicester Place accessed the Ad Lib, a club four floors above the Prince Charles Theatre. Will pressed the call button. The doors began to close, but two Beatles jammed them apart and squeezed in, followed by their wives. All were giggling and seemed to be on the verge of hysterics. Will wondered if his face was dirty or his fly undone. He was not the catalyst of the laughter, however. Judging from their glazed, illuminated eyes, the Fab Two and their consorts were in a highly altered state. As the lift began to ascend, the cackling evaporated, replaced by panic.

‘This lift’s on fire!’ shrieked George.

‘And we’re going to hell,’ howled John.

‘We’d be going down for that.’

‘Then it’s your Woody.’ John seemed surprised to find he was also smoking, in his case a Gauloise Bleue.

‘The Bismarck’s sinking!’ said John’s wife, Cynthia, who was wearing large granny glasses with blue lenses.

‘What’s that up there then, all red and crackling?’ said George.

‘Flames,’ responded John.

All four started screaming. Will felt obliged to intervene.

‘It’s a red light actually.’

This did not have the required effect. In a neat reversal of the established order, the lift door opened on two screaming Beatles and their squealing wives. The Ad Lib was a cavernous space, soundproofed by fur that lined the oak-panelled walls. The club’s dim lighting rendered the low tables, chandeliers, and faux-leather banquettes into shadowy outlines. Behind a grand piano stacked with record decks, DJ Teddy was playing imported American soul and R & B, the only genres deemed sufficiently “cool”. The clientele included a sprinkling of Stones, Who and Pretty Things, two famous cockney photographers, models, actors, dealers, and career criminals.

John had a reputation for blowing up if crossed. A path was quickly cleared as he swayed towards the private table reserved for the sole use of the Beatles. It was in an alcove, with a large window overlooking the tiled roofs of Soho. Bystanders were amazed by John’s affable manner, though this was easily outshone by George, beaming at them like a man in love.

‘Mind if I come to?’ said Will.

‘Do your own thing, man,’ grinned George.

Will followed a little sheepishly. He did not want to be thought a hanger-on. There was a definite hierarchy in the club, and the Beatles were at the summit. The nascent counterculture was feudal. Musicians exercised droit de seigneur after every gig. The serfs stood and gaped from the bar. Ringo was already sitting at the table. The two couples shook with barely suppressed laughter at the sight of him.

‘Have you been at the wacky baccy?’ the drummer demanded in his deadpan way.

‘No, wack,’ said George. ‘It’s better than that. I’m seeing God.’

‘Do say hello from me!’ John put on his upper-class voice, transforming the vowels into strangulated parodies.

‘I love everybody.’ George surveyed the dim surroundings with kaleidoscope eyes. ‘I want to hug and kiss them all.’

‘I hear the Krays are in tonight. Not sure they’d dig that,’ said Ringo.

‘Ronnie might,’ said John.

‘Who’s the fella?’

‘I’m Will. We were neighbours in Abbey Road. I was in Studio Three while you were in Two.’

‘You’re a bit long in the tooth to be a rocker,’ said George

‘I’m a sound engineer.’

‘Who were you recording?

Will mentioned an American singer with a reputation for being a firebrand.

‘He’s a nutter,’ said John.

‘Did he have a revolver?’ demanded George.

Ringo was shaking his head. It had been a case of mistaken identity. ‘I meant the fella barging through the woolybacks in our direction and making a right commotion while he’s at it.’

‘That’s our wicked dentist,’ said George.

‘They’re letting any riff-raff in these days. He’s a very groovy tooth fairy, though.’

The man was turned out in check hipsters with a wide belt, a shirt with floral prints, and a brown Carnaby leather jacket. His name was John Riley, a south Londoner who had trained in cosmetic dentistry in Chicago and set up a flourishing Harley Street practice. Known as the dentist to the stars, many of the crowns and bridges gleaming in the club owed their existence to him.

‘I see you’re keeping him to yourselves,’ said Ringo.

‘Who’d want to keep a dentist?’ said John.

‘A dentist keeper,’ suggested George.

John Riley’s florid face was steeped in anxiety, which melted at the sight of them.

‘Glad to see you got here safe and sound, boys.’

‘Shapeshift and crystal fashion,’ said John.

This reduced George and him to hysterics. Their cackling lasted long enough for Ringo to drain his scotch and coke, stub out his Rothmans, glance up at Will and say, ‘Are they always like this?’

‘It was quite a journey, wasn’t it, John?’

‘I’ll say, George. Marshmallow trees. Grenadine skies.’

‘We came by mini,’ said his wife, surprising John, who thought they had got there by submarine. ‘The Bismarck is sinking! A man of your standing shouldn’t do things like that.’

‘Yes, you’re a very naughty dentist. I’m not flashing my molars at you ever again,’ said John.

‘Or my wisdom teeth,’ said George. ‘I need as much of that as possible.’

‘Look, boys, I’m sorry. I thought it would be fun.’

Riley was referring to the LSD he’d spiked their coffee with after dinner in his Bayswater flat. He gazed forlornly at Cynthia and Pattie’s mouths, bidding farewell to the pearly veneers he had made. His practice was painless. He shot patients up with Valium beforehand. Not only was he the catalyst for ‘Doctor Robert’, but his actions that night also made him indirectly responsible for…

‘Tomorrow never knows,’ said Ringo.

‘We’re quite aware of what sort of fun you had in mind, you dirty perv,’ said John.

‘But we forgive you,’ said George, ‘cos we love you.’

There was a free seat at the table. Will asked if he could sit there.

‘Only if you don’t say anything,’ said John.

The above is an adapted version of Chapter 20 of Aleister Crowley MI6: The Hess Solution