Richard C McNeff

Author

ON THIS PAGE

- Victor Neuburg: The Triumph of Pan

- Foreword to Obsolete Spells

VICTOR NEUBURG: THE TRIUMPH OF PAN

In a letter sent to A.E. Trick in 1934, Dylan Thomas wrote: “The creature himself – I must tell you one day if I haven’t told you before how Aleister Crowley turned Vicky into a camel – is a nineteenth-century crank with mental gangrene, lousier than ever before, a product of a Jewish nuts-factory, an Oscar tamed”.

“Vicky” was Victor Benjamin Neuburg, who as poetry editor of the Sunday Referee had been the first to publish Dylan’s work. Yet far from being a solitary instance, line upon line of Dylan’s letters of the mid-Thirties explode with bile against Neuburg, his companion Runia Tharpe, and the poetry group they presided over at their home in Swiss Cottage. This was nothing new. Throughout his life, Neuburg inspired extreme reactions in those who knew him.

Neuburg was born in Islington on May 6, 1883 into a Jewish family of Viennese extraction. When he was an infant, his father returned to Austria, so his mother raised him with the help of doting aunts. At the age of sixteen and a half, he joined the family firm, which imported canes, fibres and rattans, but it quickly became apparent a conventional life was not for him. He felt the call to be a poet and nursed an enthusiasm for fads. He dabbled with agnosticism, and vegetarianism until he settled on the paganism and ritual magic of Aleister Crowley. They met while Neuburg was up at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1906. Crowley, an alumnus, who often returned to the college to fish for disciples – a ruse later adopted by the Soviet Secret Service – simply knocked on the door one day.

Aleister Crowley, the self-styled Great Beast, was born in 1875 into a strict Plymouth Brethren family and needs much less of an introduction than Neuburg. Due to the number of dedicated websites, The Observer has described him as the “demon of the internet”. New biographies and editions of his work appear monthly, which is odd when you consider that the Beast died a heroin-addicted pauper in Hastings on December 1, 1947, leaving eighteen shillings and sixpence, and a terrible reputation. Spurred on by John Symonds biography, the Great Beast, interest simmered through the Fifties, then, in the Sixties, Crowley’s appearance on the cover of Sergeant Pepper heralded his becoming an icon of the Counter Culture. His interest in the occult, yoga, drugs, his travels in the East, dovetailed with the obsessions of the period. With the arrival of Punk, his philosophy of rampant individualism, of “Do what thou wilt”, seemed to have discovered its soundtrack.

At an early age, Crowley had decided he was the anti-Christ and continued to cause mayhem throughout his life in a variety of guises, including mountaineer, writer, painter and spy. He played a great part in reviving the study of ritual magic (or magick, as he termed it, a spelling that has become ubiquitous, from the shop signs in Glastonbury to the titles of self-help manuals) and had a significant influence on Wicca and Scientology. His system is that which informs the Cabbalistic framework that underpins Under the Volcano, due to Malcolm Lowry’s friendship with a follower of Crowley. In 2003, he came seventy-third in the BBC poll of the 100 most famous Britons. In an article in the Guardian, Tim Cummings commented, “His influence on modern culture is as pervasive as that of Freud or Jung.” It is little wonder that Neuburg, who detested the “normal” and longed for an extreme magical, Dionysian mode of being, was sucked into the Beast’s orbit.

From 1906 to the eve of the Great War, Neuburg was Crowley’s foremost apprentice, sacrificing the family fortune and, arguably, his health and a fair bit of his sanity in the process.

Somewhat disastrously for a magician, Crowley lacked the capacity to witness fully what he invoked, a deficiency amply compensated for by Neuburg who had formidable talents as a seer. In the Algerian desert, with the aid of mescaline and sexual magic, they were the first Englishmen since the Renaissance to make the Enochian Calls of Edward Kelly and John Dee, court magus to Elizabeth the First. These Calls were designed to summon angels and a vivid record of their experiences was later published in the Equinox as ‘The Vision and the Voice’, which included their encounter with the dreadful Spirit of the Abyss, Choronzon. During this trip, Neuburg had his head shaved so only two pointed tufts shaped like horns and dyed red remained. Crowley led him by a chain attached to a metal collar round his neck and introduced him to bemused Bedouins as a captured jinn.

Back in London, under the aegis of Crowley, Neuburg and other followers put on the Rites of Eleusis at the Caxton Hall. Vicky demonstrated a remarkable talent as a dancer during performances in which they invoked the pagan gods, recited Swinburne and Baudelaire, and provided the audience with a mescaline-laced punch. When reading accounts of this, or the commune like arrangements at Crowley’s flat at 124 Victoria Street, where magical sexual rites and a wholesale consumption of mind-altering drugs was in order, it seems the Sixties were already thriving in Edwardian London.

During this time, Neuburg had a relationship with Ione de Forrest, a beautiful, highly-strung actor, who performed in the Rites. There is evidence that Crowley was also involved with her and was jealous of her influence on his acolyte. After one session, in which Neuburg had danced down Mars, Crowley allegedly did not bother to release him. Possessed by the god of war, Neuburg visited Ione, who was pregnant, probably by him. She spoke of killing herself. With uncharacteristic cruelty, Neuburg told her to go ahead and left. The artist Nina Hamnett found the body the next day: the actor, whose real name was Joan Hayes, had shot herself. Hamnett records all this in her autobiography Laughing Torso (Constable, 1931), in which Neuburg is referred to never by name but as the Poet. Ione’s death haunted Vicky and he believed it was a widely known story in bohemian circles, which it probably was, at least after the appearance of Hamnett’s book. Yet it was still not enough to provoke a breach with his Holy Guru.

Crowley was a charismatic man who attracted many apprentices and Scarlet Women in the course of his career, but Neuburg was of more use to him than most. Vicky’s large private income came in handy, especially in the production of the Equinox, an expensively produced magical journal that ran to several issues. Under its auspices, The Triumph of Pan (Equinox, 1910) appeared. As With Neuburg’s first collection Green Garland(Probsthain 1908), most of the poems deal with occult or mythological themes and stylistically owe much to the Greek and Roman poets, Blake, Shelley and Swinburne. Neuburg’s poetry, like Crowley’s, can seem outmoded today and it is doubtful if it would be remembered, but for their other exploits. The opening of ‘A Meeting’, dedicated to Nora, a lady of pleasure Neuburg met in Bournemouth, gives a taste of this:

“Violet skies all rimmed in tune,

Soft blue light of the plenilune

Oh, the sway of the idle moon!”

Arthur Calder-Marshall, the historian, blamed early tragedy for preventing Neuburg becoming a great poet and described him as “a Prometheus bound before he could make fire”. Rupert Croft-Cooke summarised both his poetry and Crowley’s as “nothing but a volatile facility”. Nevertheless, upon its appearance in December 1910,The Triumph of Pan garnered many reviews, several favourable (Katherine Mansfield was an admirer), and it is still in print today.* There is an androgynous slant to some of the poems, revealing the influence both of Sappho and Edward Carpenter, which is epitomised by such lines as:

“Take thou my body, now hermaphrodite.”

Neuburg dedicates most of the poems to various contemporaries, including two to Austin Osman Spare, who produced portraits of both Neuburg and Crowley. Several cast light on his relationship with the Beast. Some reminisce in occluded terms about their experiences in the desert. Others are more direct:

“Sweet Wizard, in whose footsteps I have trod

Unto the shrine of the most obscene god,

So steep the pathway is, I may not know,

Until I reach the summit where I go.”

Neuburg’s ultimate goal is a transgressive one; a Nietzschean desire to see “further than is permitted”. He is gleefully marching to the beat of a different drum with the Beast keeping time.

“Let me once more feel thy strong hand to be

Making the magic signs upon me! Stand,

Stand in the light, and let mine eyes drink in

The glorious vision of the death of sin.”

Crowley and Neuburg’s final magical operation occurred in January and February 1914. They locked themselves in a Paris hotel room and invoked a succession of gods, including Jupiter and Mercury. As usual, the results were dramatic. Shortly after, Neuburg parted ways with his master. What brought on the final breach is unclear. Vicky seemed to have come into some money at this time, which only added to Crowley’s ire as he saw this as a direct result of the Working. There was a tradition in bohemian circles in the inter-war years that Crowley had ritually cursed him, one Neuburg corroborated, turning him into a goat, however, not the camel of popular belief. Nothing the Beast himself said or wrote on the subject contradicts this. He was to describe Vicky as “a Caliban-like creature, a certain deformed and filthy abortion without moral character”. He ridiculed him in his autohagiography The Confessions (Routledge, 1979) and on June 28, 1930 penned a limerick in his diary, which showed that Neuburg was still in his thoughts sixteen years after the split:

“A sausage-lipped songster of Steyning

Was solemnly bent on attaining

But he broke all the rules

About managing tools

And so broke down in the training.”

Following it is written: “Spiritual attainments are incompatible with bourgeois morality”. ‘Tools’ probably has a sexual meaning.

Neuburg went on to fight in the First World War and by all accounts cut a ludicrous figure as a soldier. Afterwards, he lived in the picturesque Vine Cottage in Steyning, Sussex, where he set up the Vine Press. Using a handheld press, he produced several volumes of his own poetry: Lillygay (Vine Press, 1920), which included verse in Scottish dialect; Swift Wings (Vine Press, 1921), about subjects connected with Sussex;Songs of the Groves (Vine Press, 1922) and Larkspur (Vine Press, 1922), in which he occasionally broaches occult themes. He also printed the work of others, including Rupert Croft-Cooke’s Songs of a Sussex Tramp(Vine Press, 1922). The books were beautifully produced and employed a curious font with a wide W and linked double O.

In his memoirs, Glittering Pastures (Putnam, 1965), Croft-Cooke has a chapter called The Vickybird, which describes Vicky in Steyning in the early Twenties. A fuller picture emerges in Arthur Calder-Marshall’s The Magic of my Youth (Hart-Davis, 1951). His family lived in the village, and later he was to meet Crowley as well. As Calder-Marshall described him, Neuburg at this time possessed “thin venous hands and a head which, by nature disproportionately large for his body, was magnified by dark medusa locks”. He dressed scruffily and at times wore Elizabethan style leggings, which went with his general love of fol-de-rol and his use of greetings such as “Prithee, good sir, enter my humble abode.’ He had coined his very own neologism “ostrobogalous”, which he used to describe anything pornographic or odd and was prone to speaking in abbreviations, such as T.A.P., take a pew, or T.K, tobacco craving. He would go to extraordinary lengths to pick up litter or rescue insects and everyone commented on his astonishingly loud and screeching laugh.

In 1921, Neuburg married Kathleen Rose Goddard, whom he met when she worked at Hove Post Office. They produced a son, also called Victor, described by Neuburg as “my first and only edition”. Without Vicky doing much to prevent it, Kathleen, who seems to have been serially unfaithful to him, eventually ran off with someone else. With the family trust almost exhausted, Vicky’s prospects seemed bleak. What he had renounced haunted him. “He gave up magic and spent the whole of the rest of his life feeling he was not doing what he was meant to be doing,” his friend, the journalist Hayter Preston, observed. His only hope was that he would live again, as expressed in a poem of this period entitled ‘White Hawk Hill’.

“I shall return; the Green Star has me still,

Brain, body, soul and heart. My spirit’s will

From tranced sleep of splendour will be drawn

Back to the Green Star of the Golden Dawn.”

In his memoirs, Croft-Cooke speaks of Neuburg’s need to be “in the swim” and a curious series of events brought this about in the early Thirties. Neuburg met a woman called Runia Tharpe, a freethinker and weekend bohemian, who was the wife of a society portrait painter, and moved in with her – first in Primrose Hill, then in the Swiss Cottage Area. In 1933, Hayter Preston became literary editor of the Sunday Referee and gave Vicky a column called Poet’s Corner, in which, among others, he published Pamela Hansford Johnson, David Gascoyne, and Dylan Thomas, leading eventually to the appearance of the Welshman’s first collection,18 Poems. He was also prone to publishing just about anybody who sent work into him, being terrified of hurting someone’s feelings by rejection, a trait Dylan relentlessly satirises in his letters:

“A Sunday paper did its best

To build a Sunday singing nest

Where poets from their shelves could burst

With trembling rhymes and do their worst

To break the laws of man and metre

By publishing their young excreta.”

There is more, much more of this concerning “The Neuburg Academy for the Production of Inferior Verse” where Vicky “must spread the vomit evenly and impartially over his pages”. This scorn for “the Creative Lifers” and indeed for Neuburg’s whole conception of poetry, which Dylan describes as “word-tinkling” or “saccharine wallowings of near schoolboys in the bowels of a castrated muse”, did not stop Dylan contributing to Poet’s Corner or attending the meetings organised in Neuburg’s home in Springfield Street, where poets such as he himself read.

Also present was the young Jean Overton Fuller, who grew fascinated by Neuburg; enough to produce in 1965 probably the definitive biography, The Magical Dilemma of Victor Neuburg, currently republished in a third edition by Mandrake. Fuller’s impulse in writing the biography is devotion, and she is brave in facing up to features of Vicky’s personality and practices that, at the very least, must have struck her as bizarre. She describes Neuburg as “the bole from which the tree of my life had grown”. Indeed, Neuburg, a kind and genial man, largely inspired affection in those who knew him and bore the nickname Vicky or Vicky Bird, the latter due to his jerky gait. Even Dylan was fond of him and the voluminous scorn of the letters, while sincere in its criticism of a type of poetic impulse, was an example of him playing the imp. Neuburg did not stay in the swim for long. The Sunday Referee changed policy and he lost his position. His attempts to carry on alone failed. His final years were ones of eclipse. When Neuburg died of lung-related complications on May 31, 1940, Dylan described him as “a sweet, wise man” and complimented him “for drawing to himself, by his wisdom, graveness, great humour and innocence, a feeling of trust and love, that won’t ever be forgotten” – not the words of an enemy.

The years with Crowley had had a disastrous effect on Vicky’s pocket, reputation and health – Fuller believes the rigours of his magical training at Boleskine, the Beast’s lair on the shores of Loch Ness, contributed to his lung problems, and so his death. Most journals and newspapers would not accept any work from him for the rest of his life; the Beast’s increasing infamy only serving to remind editors of the association. Neuburg claimed Crowley had ruined his life and was terrified of meeting him. On a couple of occasions, the Beast had sent his current scarlet woman to Steyning and eventually came himself. Vicky hid with a neighbour. Yet Vicky never recanted and continued to believe the magic worked, just as it had in 1910, when possessed by Mars, he had predicted the First World War. Despite his fear, his feelings towards the Beast remained ambivalent. Neuburg was never sure if Crowley was the worst or best man who had ever lived. On its publication in the late Twenties, he hailed Crowley’s Magick in Theory and Practice as the greatest work on magic since the Renaissance. If the constructs of magic and poetry hold true and there is a numinous architecture, which we glimpse and sense we are here more fully to behold, Neuburg is important: he dared test the waters. Yet even in the glory days, he foresaw rupture and exile. In the last poem of the Triumph of Pan, “Epilogue”, which aptly is dedicated to AC, he wrote:

“I am weary even of song, and the lyre is cold,

And my heart is lead, and the lyre is old,

Dusk falls on the earth, and Apollo no

more comes Winging His way to me now;

it may be I shall not sing again. Yet to

the dream was I true, and I followed

the light Till it vanished…”* The Triumph of Pan (Skoob Books Publishing, London, 1989)

Ω

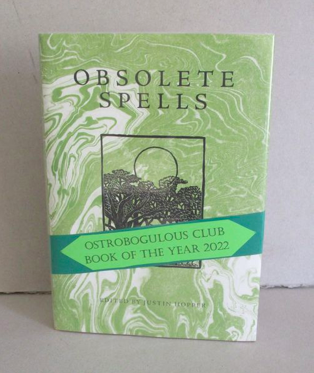

Obsolete Spells

A compendium of poetry and prose published by Victor Neuburg on his Vine Press in Steyning, Sussex.

FOREWORD

(published by Strange Attractor Press)

The more time you spend with Victor Neuburg, the more you come to like him. With his ‘thin venous hands and a head which, by nature disproportionally large for his body, was magnified by dark medusa locks’[1], it becomes natural to think of him as ‘Vicky’ or ‘the Vickybird’, as friends called him, the latter due to his jerky gait. Yet two shadows loom in which he has languished since his death. One is cast by Dylan Thomas whom Neuburg discovered when editor of Poet’s Corner in the Sunday Referee, going on to be instrumental in the appearance of the Welsh bard’s first collection, Eighteen Poems (1934). The other by Aleister Crowley, the sorcerer who held sway over Vicky for seven years from 1906. Far from liking Vicky, Thomas and Crowley took great delight in holding him in the utmost contempt.

To Crowley, the ‘sausage-lipped songster of Steyning’ is a ‘Caliban-like creature, a certain deformed and filthy abortion without moral character’. Thomas matches this vitriol, raging against a ‘nineteenth-century crank’ and ‘the Creative Lifers’, the put-down he applies to Vicky, his muse Runia Tharp and the poets of their circle, vilifying their ‘word-tinkling’ and ‘saccharine wallowings’ in several of his Collected Letters (1985).

What was it about Neuburg that inspired such scorn? His scruffy appearance? His penchant for Elizabethan style leggings with breeches and general love of fol-de-rol and greetings such as ‘Prithee good Sir, enter my humble abode’? The abbreviations he coined such as T.A.P., take a pew, or T.K., tobacco craving? The extraordinary lengths he would go to when picking up litter or rescuing insects? His loud and screeching laugh, compared on more than one occasion to a parakeet’s? Or was it none of the above, and, in the case of the Beast, high dudgeon because Neuburg threw off the shackles and turned off the money tap of family funds?

John Symonds, Crowley’s first biographer, was the widowed Runia Tharp’s lodger in Boundary Road, Swiss Cottage. Vicky’s books on magic, still lining the living room shelves, played their part in sparking his fateful interest in Crowley. The result was The Great Beast (1951) in which Symonds did little to hide his distaste for his subject. In a similar vein, Jean Overton Fuller in her The Magical Dilemma of Victor Neuburg (1965), though respectful of Crowley’s erudition, portrays him as something unpleasant Neuburg got mixed up with that she must keep apologising for. As she details their magical, homosexual, and drug-taking adventures you sense her consternation at finding the sweet, kind mentor who was ‘the bole from which the tree of my life has grown’, cavorting with his ‘inflated, pseudo-messiah’ in the most intimate of settings. Such antipathy was entirely typical of post-war Britain. Crowley was a monster, a charlatan, “the King of Depravity’ justifiably villainised by the gutter press.

Then in the 1960s, there were the first ripples of a sea change. With his use of drugs to expand consciousness and an esotericism that married East and West, the counterculture recognised in the Beast a fellow spirit, to the extent that Paul McCartney could attribute the Beatles enduring popularity to ‘…something metaphysical. Something alchemic. Something that must be thought of as magic—with a k’.[2] Symonds recorded his repugnance at this turnaround, a dismay that Overton Fuller must have shared.

How much more nonplussed would they be at the degree of rehabilitation Crowley has enjoyed in this millenium? Voted seventy-three in BBC Two’s 2002 poll of the 100 Greatest Britons; well on his way some consider to becoming a national treasure. Even more extraordinary is the academic respectability that university departments in the Unites States and Europe have conferred upon him. Scholars pore over his life and work, meticulously investigating his membership of the Golden Dawn, the creation of the Thoth Tarot, his impact on astrology and Wicca. The cosmopolitan and eclectic range of individuals on whom he cast his spell, such as the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, the Argentinian artist Xul Solar, the so called ‘father of Brazilian rock’ Raul Seixas and his collaborator, the bestselling writer Paulo Coelho, have all been held up to academic scrutiny.

Yet if anyone knew Crowley and what he was up to it was Neuburg: no one travelled further or more perilously with the Beast than Vicky. It was Neuburg who danced like Nijinsky before an audience tripping on mescaline during the Rites of Eleusis; Neuburg who was possessed of Mars and allegedly predicted the First World War; Neuburg who contributed to The Equinox, Crowley’s occult periodical, and joined in summoning the Angels of the thirty Aethyrs at Bou Saâda in Algeria, reviving the Enochian magic of John Dee and Edward Kelley. It was Neuburg who raised Jupiter in a Paris hotel room and partnered Crowley in his most audacious Workings, imbued with more natural talent on the magical plane than anyone else he had ever known according to the Beast.

The Neuburg of Obsolete Spells has settled down. He is in Steyning printing fine-looking books on the Vine Press. He is married and has a son. The turbulent years with Crowley are behind him; the period when he is once more “in the swim” as editor of Poet’s Corner is sometime ahead. The past still casts a shadow. He comes across as feeling he has strayed from his true path. He lives in fear that the Beast will prey on him, borne out when Crowley visits, banging his stick on the ground outside the door of Vine Cottage and declaring “I want Victor”. Then, according to Symonds, on no less than another three occasions when Alostrael, the Beast’s current Scarlet Woman, turns up on the threshold and theatrically bares her breast to reveal the 666 carved there, terrifying the maid who answers each time. Yet Neuburg does not recant or forswear the magic of his youth. He does not turn Catholic or take up golf. He publishes books that reflect his love of local lore and landscape, the Sussex Downs, and local history. All the generosity of old is there. He brings out Rupert Croft-Cooke’s Songs of the Sussex Tramp. He is still progressive with a horror of the normal and is drawn to anarchy and Vera Pragnell’s Sanctuary, a community of sexually liberated free spirits whose manifesto he prints. And there is still the magic: the esoteric musings of Ethel Archer’s Phantasy and that embodied in the collections of his own poetry cranked out on the press: Song of the Groves and the more landscape-imbued Swift Wings: Songs in Sussex, where in ‘White Hawk Hill’ he celebrates:

We who are burned by fire, buried in the earth,

Drowned in the water, know the secret mirth,

Sung to the stars by wandering elementals;

The Soul of all things; the true transcendentals

Deeper than death, above the need of birth.

His feelings for Crowley remain complicated. He is unsure if his former master is the foulest or greatest man who has ever lived. Despite all the damage their relationship did to his health, pocket, and sanity, he reviews the Beast’s Magick in Theory and Practice (1929) and hails it as the greatest work on magic since the Renaissance.

Crowley displays no such generosity. The Beast, in fact, seems curiously unaffected by the visionary pyrotechnics of drugs and ritual magic; the lavatorial sexual practices indulged in with scores of male and female lovers; the followers who are drawn into his orbit and then burn up like meteors. He is multi-faceted it is true: mountaineer, chess player, yogi, pornographer, spy, poet of the fin-de-siecle, occult polymath. He is witty, and the new Aeon he proclaims does bear some unsettling parallels to what has transpired since his death in 1947. He remains, however, resolutely one-dimensional, ceaselessly on the make, prone to spite, conceit, and an adolescent urge to shock. It becomes easy to agree with Christopher Isherwood, who sampled the licentiousness of pre-Nazi Berlin in his company: “The truly awful thing about Crowley is that one suspects he didn’t really believe in anything.” The only thing real about him, Isherwood concludes, is his drug addiction.[3]

Neuburg, on the other hand, is a warm, flawed human being who works tirelessly to better the lot of others, especially fellow artists, and keeps faith with the magical, free-spirited royal road of his youth. Yet here we have Thomas again:

A Sunday paper did its best

To build a Sunday singing nest

Where poets from their shelves could burst

With trembling rhymes and do their worst

To break the laws of man and metre

By publishing their young excreta.

You pinch yourself and remember that Thomas was the loudest bird in the nest, regularly giving readings at Neuburg’s home, readings that were the first steps on his path to greatness. Thomas, in fact, was acting the imp and playing to the gallery, unable to resist the temptation of sending up the foibles of his mentor. His true feelings for Vicky were more complex. When Neuburg died of lung-related complications on May 31, 1940, Dylan described him as ‘a sweet wise man’ and stated: ‘he possessed many kinds of genius, and not least was his genius for drawing to himself, by his wisdom, graveness, great humour and innocence, a feeling of trust and love, that won’t ever be forgotten’.[4] Obsolete Spells is proof of that.

[1] The Magic of my Youth, Arthur Calder-Marshall, Rupert Hart-Davis (London) 1951.

[2] Antony DeCurtis, “Paul McCartney,” Rolling Stone, 3-17 May 2007, 61.

[3] Christopher Isherwood, Diaries, ed. Katherine Bucknall, Vol. 1 1939-1960 (New York, HarperCollins, 1997), 550.

[4] As quoted by Jean Overton Fuller from the Dylan Thomas Memorial Number of Adam International Review (1953).

Made at the tip of Africa. ©