August 10, 2024

THREE MYSTERY CRASHES

Hess, Kent, Sikorski: Is there a link?

ON 10 MAY 1941, a customised Messerschmitt-110 crashed in Lanarkshire, Scotland. The pilot parachuted to safety. Upon capture, he claimed to be Luftwaffe Captain Alfred Horn. This was an alias. He was, in fact, Rudolf Hess, carrying the calling card of Albrecht Haushofer, his principal adviser, which was found on him, and almost certainly a peace treaty which vanished.

Hess’s story is notorious for anomalies. Official records are missing or embargoed. Everything points to his destination being Dungavel House, the estate of the Duke of Hamilton. Hamilton attended the Berlin Olympics in 1936, where he met Albrecht Haushofer, who described him as his closest friend and visited him at Dungavel. Hamilton was an ardent proponent of appeasement as well as being Lord Steward of the Household to George VI, on familiar terms with Churchill. Haushofer was a Mischling, partly Jewish on his mother’s side, granted immunity by Hess from the Nuremberg Race Laws. In the early years of the war, he explored several avenues for peace on behalf of his employer and the resistance against Hitler. In September 1940, Haushofer wrote to Hamilton suggesting a meeting in a neutral country. The letter was intercepted by British Intelligence.

The conventional narrative has Hess, horrified by the planned invasion of Russia and convinced the British ‘peace party’ was far stronger than was the case, flying to Scotland to negotiate directly with Hamilton. Yet why would he abandon his wife and the young son he adored, risk disgrace and a lifetime of imprisonment, on the off chance of bumping into a well-connected but not particularly influential Scottish duke?

Hamilton was not even at Dungavel. He was 52 miles away, in charge of RAF Turnhouse, now Edinburgh Airport. An unidentified plane flew into the sector at around 10 pm. It did not respond to communications, nor did it show the colours of the day. Identified as a Messerschmitt-110, its flight path would potentially take it to Glasgow, the target of devastating recent bombing raids. The consensus was that the plane should be shot down. Hamilton vetoed this, provoking a “spat” in the control room. He insisted an Me-110 would not have enough fuel to return to base so the identification must be false. Hess had fitted the plane with additional fuel tanks. No air raid sirens were sounded. The Deputy Führer was at liberty to fly on. If Hamilton wasn’t waiting for him at Dungavel, then who was?

On 9 May 1941, Prince George, the Duke of Kent, was at Sumburgh in the Shetlands. On the eleventh, he was at Balmoral. His whereabouts on 10 May have never been established. There is every likelihood he remained in Scotland, where he had a house near Rosyth in Fife. Prince George was a flamboyant individual, his youth marked by flagrant bisexuality. Hollywood film stars, Barbara Cartland, Noël Coward and quite probably Anthony Blunt counted among his lovers. On a visit to the Happy Valley set in Kenya, the Prince acquired an addiction to morphine and cocaine during a fling with Kiki Preston, an American socialite known as ‘the girl with the silver syringe’, which he kicked with the help of his brother, the future Edward VIII, whose own pro-Nazi sympathies are still delivering shocks.

Kent’s half-German mother, Queen Mary of Teck, was a keen advocate of appeasement, as initially was George VI, who opposed Churchill replacing Chamberlain. After the Abdication, Kent was widely seen as the leader of the peace party. He maintained a close relationship with Joachim Von Ribbentrop, the German ambassador, and with Princess Stephanie Von Hohenlohe, whom British Intelligence identified as a Nazi spy. He probably encountered Hess and certainly met another Reichsminister, the Estonian-born Alfred Rosenberg, while visiting Germany. A report written by Rosenberg for Hitler in October 1935 stated that Kent was involved in pro-German political manoeuvring. Rosenberg was Hess’s lunch companion on the day of the fatal flight. Has the significance of this been overlooked? In early 1939, Kent conspired secretly with his German cousin Prince Philip of Hesse, who was close to Hitler, to prevent the coming war. In July of the same year, he urged his brother the king to negotiate directly with the Führer.

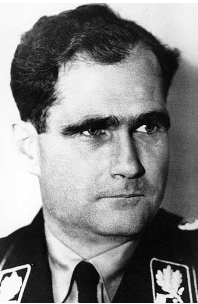

The Duke of Kent

Hamilton was informed of Hess’s capture in the early hours of May 11. Hess had been intending to land at Dungavel, he was told. There was a small landing strip on the estate beside the Kennels, an outbuilding that had been loaned to the Red Cross. As such it was neutral territory. If Hess had landed there to parlay, he would have been at liberty to fly back to Germany. Touchdown was frustrated by the arrival of a Defiant night fighter, forcing him to bale out. Perhaps not so coincidentally, Haushofer’s last peace feeler had been in late April 1941. He went to Geneva to meet Carl Jacob Burckhardt, a leading light in the International Committee of the Red Cross. Burckhardt conveyed “greetings from his friends in Britain”.

There are two alleged sightings of Kent at Dungavel. In the 1950s, a former member of the ATS claimed to a journalist she had been at the Kennels along with the duke. The report was suppressed. An employee on the estate described the landing lights being switched on in the presence of a duke whom she said was not Hamilton. In his September letter to “Douglo” Hamilton, Haushofer refers to “you – and your friends in high places.” In another 1940 letter, this time from Haushofer’s geo-politician father Karl to his son, there is a reference to “middlemen”, the Duke of Hamilton being cited as one.

According to spartacus-educational.com, Hamilton’s diary records several meetings with the Duke of Kent during the early part of 1941. The duke’s brother, Lord Malcolm Douglas-Hamilton’s secretary Elizabeth Byrd, claimed her employer told her that the Duke of Hamilton took the “flak for the whole Hess affair to protect others even higher up the social scale”. Byrd also stated that “he (Lord Malcolm) had strongly hinted that the cover-up was necessary to protect the reputations of members of the royal family”.

Hess told one of his guards that members of the British government knew of his mission. He continued to maintain he was under the personal protection of George VI, whom he, as did Hitler, believed wielded immense power akin to that of the German Kaiser. In his History of the Second World War, Churchill may well have given the game away. He describes Hess’s mission as an attempt “to get at the heart of Britain and make its king believe how Hitler felt towards it”. Hamilton is on record as nursing a lifelong grievance about the affair.

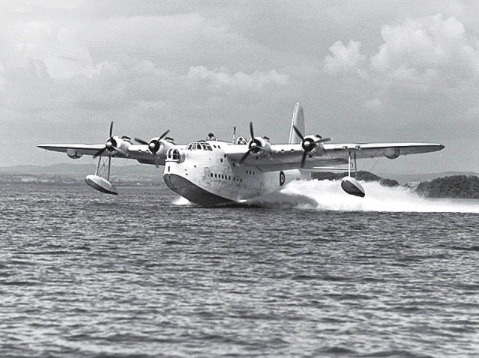

In the following year, 1942, The Duke of Kent was killed in an air crash on 25 August. The collision of his Short S-25 Sunderland Mark III flying boat with Eagle’s Rock in the Scottish Highlands at a height of around 650 feet remains a mystery. The plane was en route to Iceland where the duke, an air commodore, was due to visit the RAF base in Reykjavik. It was flown by two highly experienced Australian pilots. Their squadron leader, also a pilot, was on board, and the duke was a qualified flyer. The plane’s flight path is missing, but the standard route followed the coastline. It may have deviated inland to take a shortcut, but it is difficult to understand why it was flying so low. A flying boat over land would ascend in the prevailing conditions of poor visibility brought on by heavy cloud. Was the duke at the controls, and the more experienced crew tongue-tied by deference?

Sunderland flying boat

Though the plane possessed a rudimentary form of radar, navigation was still largely dependent on human judgement – and human error. There are many other instances of planes hitting Scottish hillsides during the war. According to Accident Investigation Branch records, 80 Sunderland flying boats were lost around Scotland, with only two downed by enemy action. Another flying boat from the same squadron crashed in the Highlands ten days after the duke’s death. Among those killed was a Glasgow journalist investigating the Eagle Rock disaster.

On impact, the 2,500 gallons of fuel carried in the wings exploded and the plane erupted into a fireball. When they found the duke’s body, his wrist was handcuffed to an attaché case that had burst open, reportedly scattering Swedish hundred-krona notes over the hillside. Just what this money was for – of no use in Iceland – remains an enigma. One exotic speculation has the flying boat on course to nearby Loch More to collect Rudolf Hess and take him to neutral Sweden to negotiate a peace deal. The duke and the Deputy Führer could finally conclude their business. A policeman at the scene claimed he found a woman among the dead. She was presumably smuggled aboard for the duke’s pleasure, though his 1934 marriage to Princess Marina and the arrival of three children suggest a happy family life.

Fifteen bodies were found, but the tail gunner, Andy Jack, had been thrown clear and survived with injuries. In hospital, he was obliged to sign the Official Secrets Act. The widowed Princess Marina visited him on several occasions. The information he gave her is believed to have influenced the inscription on Kent’s memorial which refers to a “special mission”. Similar wording was used to a family member by a pilot officer who died at the scene. Yet the morale-boosting flight was routine, one of many similar ones the duke had undertaken. Almost all the official documents that might cast light on the tragedy are lost or sealed.

The tributes and messages of condolence that poured in included one from General Wladyslaw Sikorski, prime minister of Poland in exile. He described the duke as a “proven friend of Poland and the Polish armed forces”. Sikorski was a frequent visitor to the Kents’ home and had even offered the prince the crown of Poland. One recent theory places Kent at the helm of a coup to oust Churchill, timed to coincide with Hess’s arrival. The 30,000 Polish troops stationed in Britain were to supply the muscle. It is a matter of record that Sikorski flew back from the United States on the morning of 11 May 1941. He landed at Prestwick Airport, a 40-minute drive from Dungavel.

General Sikorski

Another curious connection between Sikorski and Hess only came to light in 2005 with the publication of Guy Liddell’s wartime diaries. Liddell was the head of British counter-intelligence. The entry for 7 July 1941 records a Polish plot to attack Camp Z, the fortified country house in Surrey where Hess was being held and murder him. An MI5 file describes a gun battle between soldiers guarding the house and Polish troops. The Poles were driven by vengeance and a wish to forestall Britain signing up to Hess’s peace terms. Did a desire to silence Hess lest he reveal who was really waiting for him, including the Polish general, provide an additional motive?

On 4 July 1943, just over ten months after the Eagle Rock disaster, a Liberator II crashed off Gibraltar 16 seconds after take-off. Eleven lives were lost, including General Sikorski, his daughter, his Chief of Staff, two British officials and an M.P. Only the pilot, Eduard Prchal, survived. Though much was made of the fact Prchal was fully harnessed in his Mae West life jacket when following a common superstition among pilots he never wore one, sabotage was suspected, and blamed variously on the Nazis, the Soviets and the British. A British Court of Enquiry convened on 7 July ruled this out and determined the crash was an accident “due to the jamming of the elevator controls”. The Polish government found this unsatisfactory and conducted its own investigation which proved inconclusive. In 2008 Sikorski’s body was exhumed. The new inquiry discounted murder but did not exclude sabotage.

Liberator II

Nazi propaganda laid the blame squarely on a British-Soviet conspiracy. In 1967, David Irving published a book which touched on the possibility of British complicity, though the soon-to-be discredited historian recorded an open verdict, at least in that edition. Less hesitant was the German playwright Rolf Hochhuth, whose play Soldiers, An Obituary for Geneva, debuting in London the following year, pointed the finger directly at Churchill, desperate that his appeasement of Stalin should not be jeopardised by Sikorski’s outrage at the Soviet massacre of nearly 22,000 Polish officers in Katyn Forest. The killings took place in the spring of 1940 but were only revealed when German forces came upon the massed graves in April 1943. Hochhuth was unaware the pilot had survived the crash and was successfully sued for libel.

So what can we make of the riddle of the three crashes? Is there a link? Conspiracy theory furnishes a neat solution. The Duke of Kent was waiting for Hess at Dungavel. Sikorski was due to join them and, with Poland the casus belli, rubber stamp the treaty they would negotiate. Hess’s crash frustrated this. Kent and Sikorski’s planes were subsequently sabotaged to prevent any leaking of their collusion and the ensuing embarrassment to the royal family.

Support for this is circumstantial. Mirroring his grandnephew Prince Harry, Kent felt himself the “spare”, a sense of second-best that only increased during wartime. He was a man desperate for a role, as was Hess, who, despite his grand titles and the Reich organisations he helmed, was widely seen as “a flag without a pole”. Disgusted by the kitsch art on display at his deputy’s home on the outskirts of Munich, repelled by Hess’s obstinacy and perceived soft-heartedness, Hitler made Göring his successor. Hess’s flight was a desperate attempt to restore himself to favour with the leader he adored. Ending the war in Western Europe would have been a triumph for both the Nazi and the Duke of Kent.

Yet who could have commissioned the assassination of Kent or Sikorski? In the early disaster-filled years of the war many powerful figures in the Establishment, including some in his own Cabinet, viewed Churchill as a reckless warmonger whose policies would result in the loss of empire and the Soviet Union’s eventual dominion over Europe. Might he in turn have been intent on liquidating those suspected of being in league with the enemy?

Churchill was no stranger to ruthlessness. He advocated the summary execution of the Führer and other leading Nazis. Yet it strains credulity to believe he was party to the killing of a man he eulogised in the Commons as “a gallant and handsome prince”, or of a close wartime ally, whose successors were projected to be far more hardline when it came to the Russians. Were others hiding in the shadows who did not share his scruples?

During a supper in the Kremlin on 6 November 1944, Stalin toasted British Intelligence for having inveigled Hess to come to Britain. Churchill roundly dismissed this. Stalin took this with good humour and pointed out that his secret service often kept secrets from him. In January 1941, a British-based Finnish art historian, Tancred Borenius, visited Carl Jacob Burkhardt in Geneva. Borenius was connected both to Sikorski and the royal family. Available evidence indicates he was there to put out peace feelers on behalf of the latter and MI6. In the same month, an MI6 major called Frank Foley, who was to be chief interrogator of Hess at Camp Z, went to Portugal to talk up the “peace party” and lure a top-ranking Nazi to Britain. Was Churchill privy to these missions?

Sir Stewart Menzies, who as ‘Control’ ran MI6, passed all the code-breaking intelligence from Bletchley Park to the prime minister. He may also have revealed the secret channel he had to Admiral Canaris, the disaffected head of the Abwehr, German military intelligence, and the warning of Hess’s flight that came via this. Is it pertinent that Menzies was allegedly implicated in the assassination on 24 December 1942 in Algeria of Admiral François Darlan, commander-in-chief of the Vichy armed forces? ‘C’ hardly ever left London in wartime but, oddly enough, was in Algiers at the same time.

Evidence may one day surface that resolves the mystery of the three crashes. In the meantime, we are like the seventeenth-century polymath who wondered what songs the sirens sang: grappling with puzzling questions that are not beyond all conjecture.

This article grew out of my research for Aleister Crowley: MI6: The Hess Solution. Click on the book title for more information.